By Dina Newman

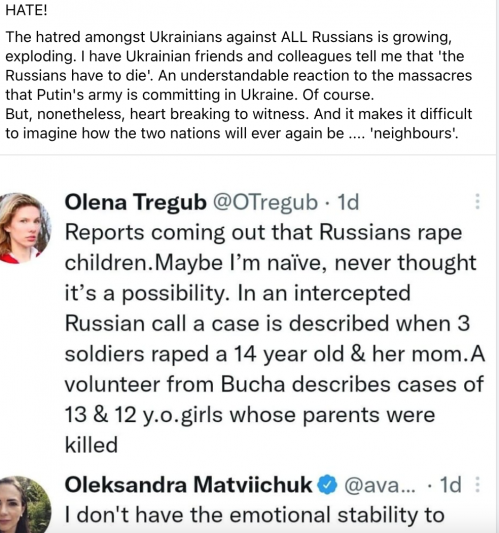

The evidence of atrocities committed by the Russian army in the towns of Bucha and other locations around Kiev could not but bring about a storm of furious Facebook comments from Ukrainian users. Many are now calling for Russia to be destroyed forever.

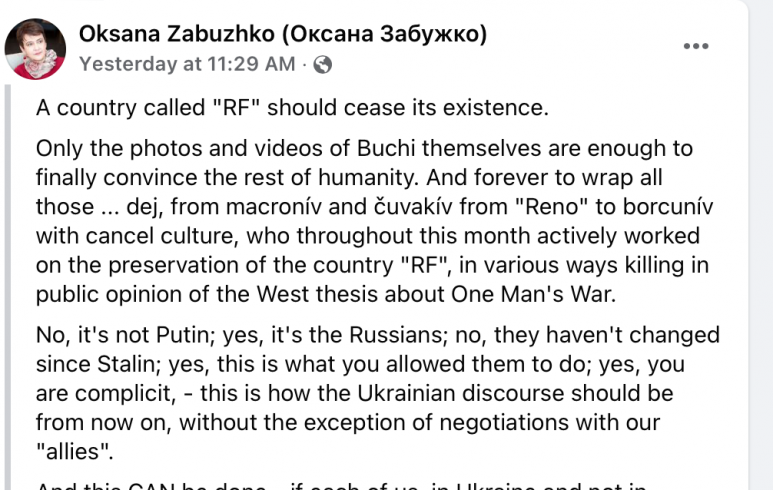

In a widely shared post, Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko called on her government to take a tougher stance towards Russia when negotiating with Western countries:

“A country called “RF” should cease to exist…. No, it’s not Putin; yes, it’s the Russians; no, they haven’t changed since Stalin; yes, this is what you allowed them to do; yes, you are complicit, – this is how the Ukrainian discourse should be from now on, without the exception of negotiations with our “allies”.

Among the typical comments under her post there are calls for “Russia to be destroyed” and to be “completely isolated from all humanity”.

“Let the whole world see this disgusting face of all the inhabitants of Russia, Putin gave the call, and our “brothers” came and killed our people, raped our children and women … I now have such hatred for all Russians that I could go up in flames!”

For the first time in the company’s history Facebook is not censoring these expressions of hate. It pioneered this policy in mid-March when Reuters first reported leaked internal emails from Facebook. The emails allowed to relax Meta’s policies on hate speech in order to let Ukrainians express their hate towards the invaders. Initially calls for death to presidents Putin and Lukashenka were allowed. The new policy as reported by Reuters was meant to affect not only Ukraine, but also Russia, the Baltics, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Neither Belarus, nor any of the Central Asian countries were mentioned in this context. Also, the new policy was reportedly extended to Slovakia and Hungary – but not to any other countries of the former Soviet bloc.

The initial policy as reported was met with scepticism by most observers, while some called it “infowar own goal”. The new hate speech rules seemed vague and inconsistent. They were meant to target Russian soldiers, but not Russian civilians or prisoners of war – a distinction which has inevitably turned out too subtle in the context of the invaders’ growing brutality.

Several problems with Meta’s new ruling became evident in the next few hours. Calling for death of the heads of states was one problem. Geographic inconsistency also needed clarifying. Meta changed its policies several times before it eventually settled for the version as quoted by its president for Global Affairs Nick Clegg on Twitter.

The ban on hate speech was lifted only for Ukraine, and only in the context of the invasion. Calling for death of Putin and Lukashenko was banned. Calling for violence against Russian civilians remained banned. Nick Clegg assured everyone that Meta would not tolerate Russophobia. But in the next couple of weeks, as Russia continued its brutal assault, all those caveats have been brushed aside.

Russians yes – But which Russians?

Those who know Russia are aware that ethnic Russians (“russkie”) are not the same thing as Russian citizens (“rossiyane”). Meta’s instruction as quoted did not differentiate between the two. This could be partly due to the language: the distinction does not exist in English, nor in Ukrainian. Yet Russia is comprised of about 190 ethnicities. Currently some Chechens, Buryats and other non-Russians are fighting in the Russian army. But over centuries, millions of Russian citizens who are not ethnic Russians, have seen their ethnic, cultural and linguistic identity repressed by Moscow’s colonialist policies. Their experience is similar to that of Ukrainians during the Communist regime. Going forward, Ukraine’s fight against Moscow’s aggression could inspire a call for decolonisation within Russia itself. Many ethnic minorities within Russia are struggling to preserve their identity. In 2019, in a shocking and unprecedented step, one professor set himself on fire in protest against marginalisation of his native Udmurt language.

Just as there are millions of ethnic non-Russians living in Russia, there are millions of ethnic Russians who are not Russian citizens and who live mostly outside Russia. Many condemn Russia’s invasion and are currently helping Ukrainian refugees. But Ukrainian hurt goes deep. In the words of one Ukrainian Facebook user: “They are all the same. They are all guilty. Even those Russians who live in peaceful Canada and continue to justify Russian “culture” – they are also to blame”.

Unintended Consequences of Meta’s new ruling

In Russia, Facebook has always been seen as a platform for liberally minded people, and many of the platform’s users oppose the invasion. After the introduction of the new hate speech policies Russian authorities declared Meta an extremist organisation and blocked Facebook and Instagram, but not Twitter. However, having an account on Facebook is not illegal in Russia, and residents of Russia who oppose the Kremlin still access Facebook via VPN services. And – here’s the surprising twist – now Meta bans THEM for expressing their hate, anger and shame over the Kremlin’s policies.

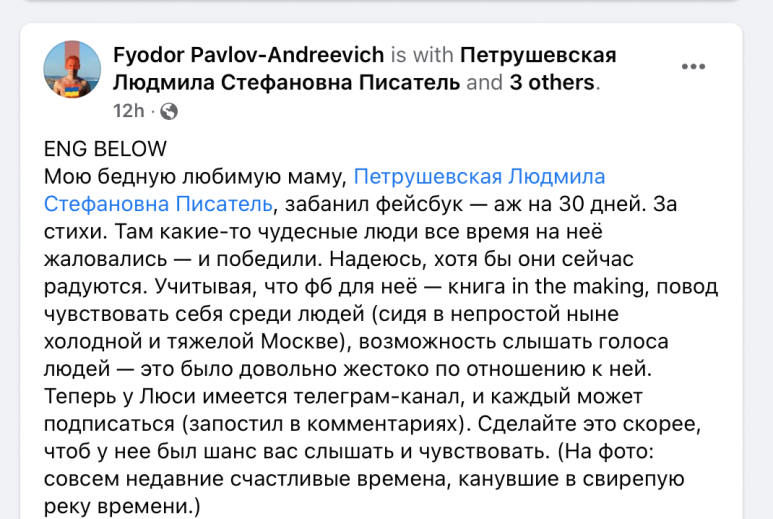

An 84-year-old writer Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, based in Moscow, has been posting her anti-war comments for over a month. She was banned from Facebook, and her son called on her audience to connect with the writer on Telegram: “My poor beloved mum has been banned from Facebook for 30 days for her poetry. Some people kept complaining about her, and have finally got their way. This is tough on her as she is stuck in cold, heavy Moscow, and Facebook was her only way of making her voice heard”. Luckily Meta overturned Petrushevskaya’s ban after a few days.

Outside Russia, anti-war protesters can access Facebook without any problems – but still risk being “restricted” for expressing hatred towards the Kremlin. A popular Russian journalist and poet, Alexander Smirnov, who writes under a pen-name Delfinov, lives in Europe. He has posted several powerful poems in protest against the invasion. His account was restricted after several poems had been found containing hate speech. In most cases the ruling was overturned after Delfinov complained to the moderators. Today, only one of his poems remains banned. “My Facebook account remains restricted, supposedly for numerous violations, while only one of my poems is banned!” – says Delfinov. “I have to say, they are at least trying to get it right: they have forgiven most of my “sins” except this one”.

Can Meta ever get ‘hate speech’ right?

Looking at the problems with Meta’s current hate speech policy around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is tempting to come up with lessons to be learnt and recommendations on how to do it better.

However, Prof Eric Heinze of Queen Mary University, London, who is an expert on hate speech, argues that there is no right way to regulate it on social networks, and whatever rules are imposed will always be vague and inconsistent.

“Many people think that some rule is out there, we just need to find it. This is very much the thinking in the European Commission, in the United Nations, in the human rights groups, – they all think, well, yes, maybe it’s not perfect but we can work on these hate speech bans…. I am very sceptical about that. Let’s break the illusion that we just need to get the right rule,” Prof Heinze tells Media Diversity Institute.

Social networks are global, yet conflicts and social contexts are local, he argues. Any generic policy against hate speech will turn out either simplified and misleading – or inconsistent.

“To formulate a rule would mean you are somehow above politics – but you are never above politics in these situations”, he says.

While universal rules may be impossible to impose globally, Facebook’s recent role in inciting violence against Rohingya in Myanmar clearly point to the power – and the danger – of hate speech on social networks.

Going back to the current wave of hate against Russians on Facebook, Ukrainian journalist Anna Filimonova notes that these feelings, while understandable, are not what will ultimately take the two countries forward. Speaking on the joint Russian-Ukrainian podcast, Kavachai, she says:

“I cannot blame my compatriots, their soul is torn to shreds after the events in Bucha, of course they now want to pour concrete all over Russia, or to turn its territory into a giant sea. I cannot possibly demand empathy from them, they have the right to be as hateful as they can be. But if we look at it rationally, Ukrainians have every interest in Russia turning into a normal country…. If Russia doesn’t manage to change, it will be very tough for Ukraine.”

Photo Credits: nikkimeel / Shutterstock