By Sandor Adam Gorni, a PhD candidate in political science at Stockholm University.

This article is in partnership with CHASE.

In June, many countries celebrate Pride Month, a time dedicated to LGBTQIA+ rights. Celebrating queer culture and the hard-earned progress toward equality often concludes in a colourful pride parade through city streets. In Hungary, however, this year will likely be different. The government has banned the 30th Budapest Pride Parade. But this isn’t just about cancelling one march, it’s about dismantling the fundamental democratic and human right to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression and targeting a minority already under political attack.

Pride began as a political protest. The global movement commemorates the Stonewall uprising of June 1969, when queer people stood up to police violence and demanded dignity. Since then, pride has become both a celebration and a political statement: a claim to public space, visibility, and human rights. It celebrates queer culture and the achievements of LGBTQIA+ communities, while highlighting the challenges that remain. In Hungary, the parade has been a vital symbol and opportunity for visibility since 1997, which has been the country’s largest recurring human rights demonstration.

Despite important progress in many parts of the world, such as marriage equality, legal partnership recognition, and expanded transgender rights, there is clear evidence that contestation of the rights of sexual minorities is on the rise. Populist far-right actors globally are increasingly mobilising anti-LGBTQIA+ and anti-gender rhetoric. They are shaping policies to undermine gender rights and forming international alliances. While Russia has long been considered the emblematic case, populist parties even in the so-called West are now following a playbook quite similar to President Putin’s in the early 2000s.

Earlier this year, Donald Trump signed an executive order prohibiting federal recognition of gender identity, enforcing a fixed male-female binary under the name of protecting women from what they call gender ideology. Similarly, in several EU countries, including Italy, Bulgaria, the Netherlands, Romania, and Slovakia, there have been efforts to restrict LGBTQIA+ content in education and, as in Italy, to limit parental rights to same-sex couples. Most of this is being done in the name of child protection. But among them, Hungary has emerged as a frontrunner.

Since Viktor Orbán came to power in 2010, Hungary has undergone significant democratic backsliding. Orbán’s so-called illiberal democracy has been undermining the rule of law, dismantling checks and balances, capturing the media landscape, and has been continuously restricting civil society and NGOs. Populist actors thrive on creating enemies. Orbán has systematically turned people against immigrants, the European Union, George Soros, and, most recently, the LGBTQIA+ community. These groups are framed as existential threats to Hungarian identity and, the government’s new favourite buzzword, to sovereignty.

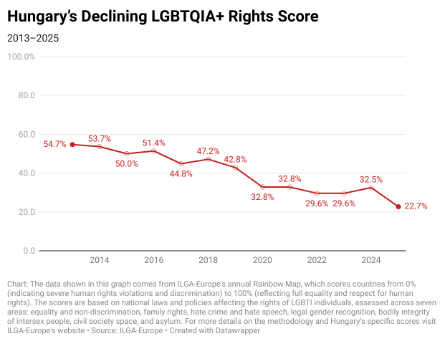

Besides political communication discourses, however, the Orbán government has translated this rhetoric into laws. In 2011, a new Constitution effectively banned same-sex marriage. In May 2020, legal gender recognition for trans and intersex people was revoked. Later that year, the Constitution was amended once again to exclude same-sex couples from the definition of family, and same-sex adoption was effectively banned. In June 2021, the so-called Child Protection Law prohibited any content which depicts LGBTQIA+ identities to minors.

Now, in 2025, the government has taken a step further. Using the same child protection discourse, Hungary has banned the Pride parade. According to legislation passed this spring, authorities can prohibit public events which depict non-traditional gender roles or non-heterosexuality. Organisers and attendees risk fines of up to 500 euros. Furthermore, the law allows the use of facial recognition technology to identify participants. This act technically criminalises public expression of LGBTQIA+ identity and silences the visibility of sexual minorities, all in the name of protecting children.

As a response to the new legislation, recurring demonstrations took place in the capital, including protests that blocked major bridges in the capital. The Mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, a member of Párbeszéd (a green-left opposition party), criticised the legislation as an act of hatred and an attack on fundamental freedom. Meanwhile, twenty EU member states have signed a joint declaration urging Hungary to revise the legislation, emphasising that it violates core EU values: human dignity, freedom, and equality. The European Commission has also called on Hungary to withdraw the bill. While the future of Budapest Pride remains to be seen, organisers have scheduled for the 28th, regardless of the new law.

Some observers argue that this new legislation will work as political theatre, a wedge issue meant to divide the main opposition party, the TISZA Party, which is now leading in polls. TISZA draws support from across the ideological spectrum, and provoking culture wars could polarise its voter base. While this may be partially true, it would be a mistake to treat the Pride ban as a mere strategy. The march represents a vision of a democratic society grounded in pluralism and fundamental human rights.

And here’s the thing: when a government limits the right of a group of citizens to peacefully assemble, it isn’t just violating the rights of that group but of everyone’s fundamental democratic rights. Even if someone is not part of the LGBTQIA+ community, this law affects them. If the state can silence one group today that it disagrees with, it can silence another tomorrow.

That’s why Pride March matters. It is not only about queer identity alone. It’s also about the freedom to be visible, to exercise fundamental democratic rights, to participate, to demonstrate and to express who we are and what we think. There can be no free Hungary without Pride.

Hungary is showing the world how LGBTQIA+ rights can be dismantled within a short period of time, even within the European Union. As legal restrictions, hostile rhetoric and hate crimes continue to rise globally, the message is clear: rights once thought secure can be undone. That’s why what happens in Hungary should concern all of us.

This article was produced as part of CHASE – Combatting online HAte Speech by engaging online mEdia – aims to define and respond to the challenges of tackling online gender-based hate speech in Cyprus, France, Greece and Italy. A project supported by the European Union. The views expressed in this text are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.