By Zorro Maplestone

Two french police employees killed in Avignon and Rambouillet; a neo-nazi terrorist plot in France’s East; and former and current military threatening a coup if “social disintegration” is not halted: France is once again at a new level of tension, in the difficult context of emergence from the pandemic and its attendant economic crisis. However, despite repeated denouncements by the academic, scientific, and international communities, the French government, right-wing opposition parties, and the media continue to push the message that “islamogauchisme”, which is commonly translated as “islamo-leftism”, would be the biggest threat to French society. The term “islamogauchisme” originated in a 2002 book by French political scientist Pierre-André Taguieff, “The New Judeophobia”. In this work, Taguieff purports the existence of an ideological alliance between Islamist networks infiltrating France and the UK (a shadowy, violent, external enemy) and leftist academics and intellectuals (an elite, conspiratorial, internal enemy) in the fight against capitalism.

More recently, on 14 February, Higher Education and Research Minister Frédérique Vidal caused a scandal when she expressed that “islamo-leftism blights society as a whole” and asked that the French national research authority conduct an investigation on the phenomenon. This was the third time in four months since the horrific murder of teacher Samuel Paty that a sitting government minister used this term, thereby giving it substantial legitimacy and reach. In reaction, Dr. David Chavalarias – a mathematician who uses extensive quantitative analysis of social media posts to investigate French political trends published a study analysing the history, scope, and effects of the rhetoric of “islamo-leftism”.

Through the analysis of over 290 million tweets with political connotations posted since 2016 by over 11 million Twitter accounts, Dr. Chavalarias’ team collected several key concepts associated with the term’s use: “traitor, enemy of the republic, immorality, corruption as well as menace, insecurity, danger, alliance with the enemy and of course compromise with radical islamism.”

Their conclusion is clear: “The term ‘islamo-leftism’ is above all an ideological weapon used in hostile discourse to discredit a political community independently of the reality it is supposed to designate.” [italics and bold in original]

While government ministers provoked the recent “islamo-leftist” polemic , it is vital to consider the role the media has played in amplifying this narrative in recent months. Europe 1, CNews, Le Point, Le Figaro, all these far-right or center-right leaning media have surfed this wave of outrage, and even respected centrist institution Le Monde has not hesitated to publish op-eds decrying “islamo-leftism”.

Rim-Sarah Alouane, a French legal scholar and PhD candidate, explains one reason for this wide promotion of the concept:

“I believe that anti-Muslim bigotry is a business today, really. It brings audiences, it plays with peoples’ fears. The more polemic you are, the more money you bring,” she tells MDI.

To support this, she cites “Fear Inc.“, a report by Daily Beast columnist Wajahat Ali, which blew the whistle on tight connections between American foundations and right-wing think tanks, collaborating to promote anti-Muslim sentiment in the public discourse and how they have profited from the resulting rise in hatred.

“Essentially those media basically want to create a buzz,” says Alouane, citing controversial 24hr news channels such as CNews and BfMTV,

“[they] take like, some polemicist, some author who can talk about covid, about islam, about pension reform… They are not really experts, they are just common pundits. But unfortunately, they’re good for the audience. They boost the audience and they make money. And I think that’s the drama here. It’s how hatred can make money, and I think that it has to be countered at some point.”

However, Dr. Philippe Marlière, a professor of French and European Politics at UCL, argues that this explanation, while correct, is ultimately “superficial”:

“It misses the extent to which some people in the media are very eager to push forward that kind of agenda. If you take, for instance, a private, 24hr a day news channel CNews, which belongs to Bolloré. He is seen by his critics – and I don’t mean just the far-left critics but mainstream critics, people who know the media and are serious about that – as playing that kind of game: of making ideas which until recently were not mainstream and making them mainstream. And notably things which used to belong to the extreme-right. Issues of islamophobia and racism.”

Yet for Dr. Marlière, the problem is not solely limited to the most extreme of France’s media:

“And then you have all the other media which without really being so clear and open about that, are using the terms in an uncritical manner, which is I think bad enough.”

Dr. Marlière bemoans the lack of fact-checking and investigative journalism on the subject:

“I’m afraid that very few journalists in France do that. So for that reason all these culture wars around ‘islamogauchisme’ have gained momentum for no reason.”

So what, exactly, is the political purpose behind promoting these dangerous accusations of “islamo-leftism” in the right-leaning media? And why now, after almost two decades of the terms’ existence, would government ministers choose to use it?

For Dr. Chavalarias, the answer is clear: With the 2022 présidential élection on the horizon and plummeting popularity scores, Macron’s incumbent party – which can be abbreviated as LREM or translated as The Republic on the Move – is worried about a scenario in which it is unpopular enough to be absent from the second round of the Présidential vote.

“Like in 2017, political parties seem to have come to terms with Marine Le Pen’s presence in the second round,” the analysis explains. “To win both rounds, LREM will therefore have to eliminate LFI [left-wing party] in the first round, which is currently its most structured opponent outside of RN [Le Pen’s extreme-right party], then beat the RN in the second round.” Accusations of “islamo-leftism” would therefore serve to hit both of these opposition birds with one stone: “Giving credit to the existence of an “islamo-leftism” is both weakening LFI and keeping pace with the extreme-right” concludes Dr. Chavalarias.

For Rim-Sarah Alouane, this strategy is clearly visible in Macron’s mixed reactions to his ministers’ salvoes against “islamo-leftism”:

“Emmanuel Macron disavowed his Minister of Higher Education, but he didn’t disavow Jean-Michel Blanquer when he said the exact same thing a couple of months ago, he didn’t disavow Gerald Darmanin who said the exact same thing as well.”

Alouane’s final conclusion converges with Dr. Marlière’s:

“[Macron] is playing both sides and I think it’s really unhealthy for our democracy.”

However, beyond Macron and his government, for Dr. Chavalarias and his team, this smear operation is the fruit of years of work by a more sinister force: The French Alt-Right.

The Alt-Right – an umbrella term for far-right movements associated with the election of Donald Trump and the Christchurch attack – have been shown to be active in French politics, both in support from overseas and in a growing French branch of the Alt-Right.

The Politoscope analysis shows that there is “a quasi-perfect parallel between the strategy of the American Alt-Right and that which underpins the promotion of the notion of ‘islamo-leftism’ since 2016.”

“The de-legitimation of muslims and immigrants mutually reinforces the de-legitimation of liberals,” explains Chavalarias through the citation of a study of the Alt-Right’s rhetoric by McLamore and Uluğ (2020). “These two processes could facilitate support for the escalation of violence, as prior research in social psychology establishes a link between perceived menace and support for the escalation of conflict and future violence within violent conflicts.”

While the rhetoric of “islamo-leftism” has not yet manifested this violent threat, the recent events have multiplied its spread through public discourse:

“According to our measurements, the ministers of the government have succeeded in doing in 4 months what the extreme-right has struggled to do in more than 4 years” explain Dr. Chavalarias and his team: “[S]ince October, the number of tweets from [the majority of non-explicitly political accounts] mentioning ‘islamo-leftism’ is superior to the total number of mentions from 2016 to October 2020.”

As well as Rim-Sarah Alouane, Dr. Marlière concurs:

“It’s working absolutely beyond all expectations. And that’s the problem, the French media are at present saturated by this sort of fake news, wrong stories, culture wars. And of course you might wonder then: To what extent does it impact upon people who watch them?”

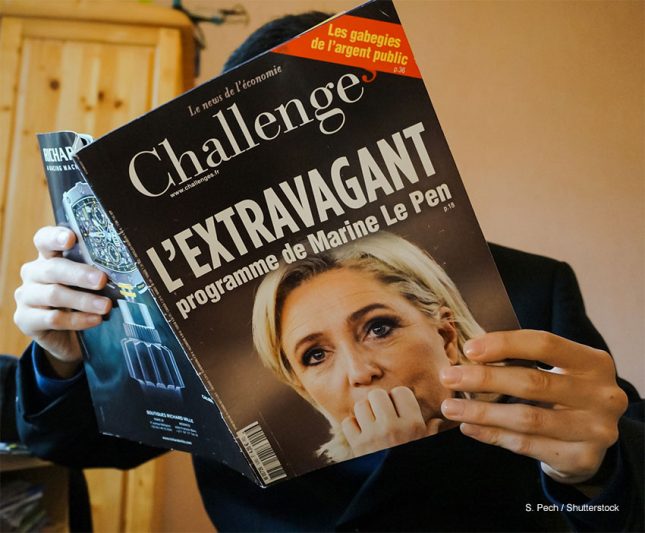

Photo Credit: S. Pech / Shutterstock