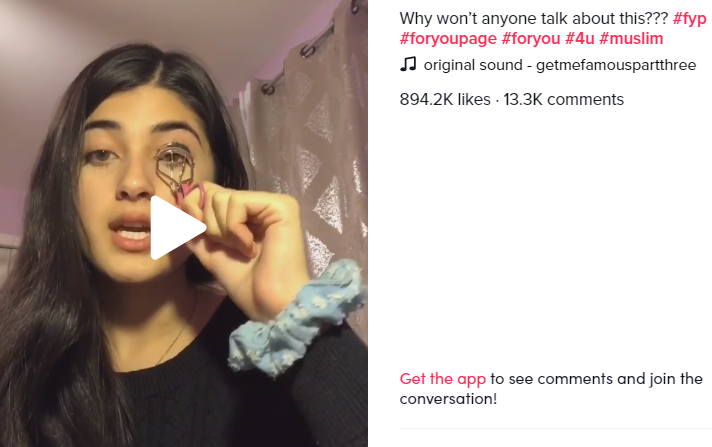

“Hi guys, I’m going to teach you guys how to get long lashes”, Feroza Aziz says to the camera whilst holding up an eyelash curler. This is not a regular makeup tutorial though, as Ms. Aziz continues: “Use your phone that you’re using right now to search up what’s happening in China, how they’re getting concentration camps, throwing innocent Muslims in there, separating their families from each other, kidnapping them, murdering them, raping them, forcing them to eat pork, forcing them to drink.” The video, which has over 890.000 likes, was posted on popular video-sharing platform TikTok and was removed from Ms. Aziz’s account. According to TikTok, this removal was a mistake and due to a past video on Ms. Aziz’s; however, many people have speculated that the video was removed due to the subject matter: Xinjiang and the detention of Muslim Uyghurs in the Chinese region.

TikTok is a relatively new social media platform but has quickly risen in popularity, mainly amongst young people. It is a platform where users can share and consume short-form mobile videos and TikTok’s mission, in their words, is to “inspire creativity and bring joy.” It was the 4th most downloaded app worldwide in the second quarter of 2019, and has an average of 500 million monthly active users. TikTok is a Chinese-owned application and was launched by Chinese technology company ByteDance in 2017. ByteDance had at that point already launched a similar application within China called Douyin, which is still popular in the country today. TikTok’s strong connections with China have caused some apprehension around the app’s data storage and how that data is used. In a recent official statement, the company tried to offer some transparency on this: “We store all TikTok US user data in the United States, with backup redundancy in Singapore. Our data centres are located entirely outside of China, and none of our data is subject to Chinese law.” Despite these assurances, the United States military along with the Coast Guard and Air Force recently decided to ban TikTok on government-issues devices, sharing that this was because of “increasing concern about possible security risks related to the popular video app’s Chinese ownership.” It begs the question why these steps were taking despite TikTok’s official stance, and whether the general public should be just as wary.

Censorship has been another big discussion around TikTok, with Ms. Aziz’s video removal kick-starting further debate and investigation. In September 2019, Guardian journalist Alex Hern revealed leaked documents which showed how TikTok provided it’s moderators with specific instructions to remove content mentioning Tiananmen Square, Tibetan independence, or the banned religious group Falun Gong. According to Hern, the documents clearly show how TikTok is “advancing Chinese foreign policy aims abroad through the app.” ByteDance responded to the leak and shared that the documents were no longer in use and that a new set of guidelines, which they did not share, took a more localised approach to moderation. However, renewed accusations of censorship on the platform surfaced in regards to the Hong Kong protests, and the lack on related content on TikTok.

Hong Kong has seen ongoing anti-government demonstrations since June 2019 and were initially organised in response to a bill which would allow extradition to mainland China. The bill has since been revoked, but demonstrations have continued with protestors calling for full democracy for Hong Kong. China has heavily censored coverage on the protests within China, painting those taking part as “violent assailants” who are “totally intolerable.” Researchers are worried this censorship has also applied to TikTok.

Writing for the Washington Post, Drew Harwell and Tony Romm outline the vast difference between Twitter and TikTok when you search for #hongkong. On Twitter, you will find countless posts about the protests, police crackdowns and content from both pro-China and pro-democracy marchers. TikTok shows a different side; the platform seems to host only food photos and fun selfies taken in Hong Kong, with very little content related to the protests. This stark contrast has raised some red flags, with Harwell and Romm explaining that “researchers have grown worried that the app could also prove to be one of China’s most effective weapons in the global information war, bringing Chinese-style censorship to mainstream U.S. audiences and shaping how they understand real-world events.” It is possible that the lack of protest-related content on TikTok is because those involved with them in Hong Kong stay away from the platform due to its ties with China; however, many are not convinced that this is where the story ends.

With TikTok still being a relatively young platform, it will likely take some time before its operating mechanisms are fully understood. On the surface, TikTok provides a space for people to create fun and simple content and can, as was seen in Ms. Aziz’s case, also provide a platform for spreading awareness and making education go viral. But the application’s close ties with China cannot be ignored and in a world where data is evermore precious, a close eye must be kept on TikTok’s data handling, and alleged censorship.