By Matteo Pascoletti

In recent weeks, the killing of Alika Ogorchukwu, a disabled street vendor of Nigerian origin, sparked an international outcry. The man, 39, was killed in the Italian city of Civitanova Marche, while some people filmed the incident. The alleged perpetrator, Filippo Ferlazzo, appeared to violently attack the victim after Ogochukwu had approached the man’s girlfriend, inviting her to buy something.

The prolonged violence of the footage as well as the passive crowd that watched without intervening (a version that has however been questioned) has contributed to the outrage. The region where the crime occurred, Marche, is also known for episodes of racially motivated violence, such as the 2018 Macerata shooting committed by Luca Traini. The list of violent crimes against POC in Italy is far from short, alas.

Whenever a white person – usually a man – commits a crime against a person of colour or a member of another marginalised group, Italian media coverage displays a series of recurring patterns. This case made no exception.

First off, there’s an overarching tendency to adopt the perpetrator’s point of view. For example, headlines tend to quote statements by the accused, or from sources close to them. Reports often lack references to when the statements were made, or their context (a police interrogation? Are they statements by their lawyer? Interviews?).

The perpetrator is therefore shown as vulnerable, suffering or repentant, thus establishing an emotional connection with the audience. Other elements, such as Filippo Ferlazzo’s mental health condition[1] were treated with tabloid-like sensationalism, despite the fact that, from a legal point of view, they might have not played a role in the murder – thus showing also blatant ableism. Even the interview with the man’s girlfriend espouses the perpetrator’s perspective, instead of showing an independent point of view.

A second pattern is that of avoiding with surrogate debates any effective accountability of power structures – such as institutions, political parties and so on. So one of the main concerns is usually to avoid the ‘weaponization’ of the crime. When this happens, the debate almost exclusively involves white people. An example of this comes from the news show ‘Zona Bianca’ that dedicated an episode to he incident. In the show’s promotional tweet below it is visible that the does not include anyone from the Italian Afroitalian community.

L’omicidio di #CivitanovaMarche è stato strumentalizzato dalla politica?

A #zonabianca il confronto tra @AlessiaMorani @alesallusti e @SardoneSilvia pic.twitter.com/nlKbfc5nCE— Zona Bianca (@zona_bianca) August 1, 2022

Alternatively, the media give a lot of space to benevolent initiatives by local administrators, such as the creation of a fund for Alika Ogorchukwu’s family. Or they debate about controversial elements of the case, such as the people who attended the murder. While the murder is talked about, the real focus seems elsewhere.

One of the most insightful comments on the murder of Alika Ogorchukwu came via Facebook, from the Italian-Somalian writer Igiaba Scego, who spoke of a ‘wrong debate’. ‘There has been a lack of debate on the laws that regulate immigration,’ she told the Media Diversity Institute.

‘It is the Bossi-Fini law that forces people like Alika Ogorchukwu to live in continuous precariousness and exposure. It could have happened in any situation, I think that this law makes bodies even more fragile. We cannot have a law that blackmails immigrants and relegates them to only one function, being working arms without recognising them as citizens, she continues.

Laws harshly shape the lives of immigrants in Italy and how they are perceived, according to Scego. ‘Security’ and ‘decency’ are buzzwords widely spread through the media over the past decades when talking about immigration and poverty. These buzzwords have been associated with laws that made city centres places for ‘respectable’ people, thus creating first and second-class citizens. Therefore, when a violent crime occurs, politicians become engaged in a ‘race to make themselves look good, or make themselves look tough, without seeing the complexity of the picture‘ says Scego.

There’s a security problem in Italy, but for migrants, because migrants and Afrodescendants bodies are in constant danger. I’m Black, I know that very well. Your body is read in many ways, and it can be read very wrongly. You live in constant fear, in constant dread,’ she says.

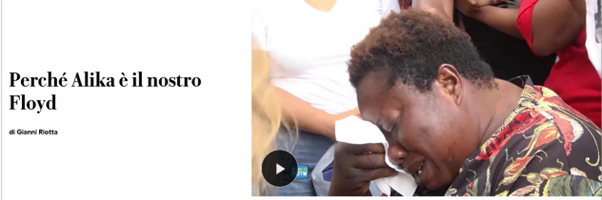

One of the aspects missing in the Italian media, according to Scego, is the ability to cover the urban context through local reporting, with the exception of the big cities. ‘I think that Italy is seen from the newsrooms of the big cities, without knowing local realities,’ she says. So, opposite to the perpetrator’s point of view, we can find moralism out of context and high-sounding comparisons, for example with the murder of George Floyd, instead of properly addressing the country’s racism in a targeted way. A different kind of sensationalism, but still sensationalism.

The gap between the local dimension and national coverage is something that also struck Oiza Q. Obasuyi. A junior researcher at the Italian Coalition for Freedoms and Civil Rights (Coalizione Italiana per le Libertà e i Diritti Civili) and an expert on immigration policies. Obasuyi lives and studied in the region of Marche, between Ancona and the University of Macerata. On 6th August, she attended the protest for Alika Ogorchukwu organised by the Nigerian community and the Italian Antiracist Coordination (Coordinamento Antirazzista Italiano). She noticed that media coverage occurred ‘mainly at a local level’, as opposed to the coverage given to the murder of Alika Ogorchukwu.

The first part of the event again called for ‘no instrumentalisation’. While this plea makes sense coming from the man’s family, as they are concerned about keeping the trial away from political influences, for Obasuyi such appeals from institutions ‘have a veil of hypocrisy’. ‘There is a context of systemic racism in which Alika Ogorchukwu died,’ she says.

‘We have these heinous episodes of racism that are therefore more easily condemned, but everything that comes before them, such as the debate about the cultural and political context, why does it never happen? There is always a veil of denialism, so we conclude it’s just an individual heinous case and Italy is not racist,’ she says.

The main effect of this approach is to make invisible political subjects and communities. These become objects of discourse and arguments, exactly as with the aforementioned habit of giving prominence to alleged perpetrators. ‘In these cases, another form of violence is done to the victim, who is invisibilised for the second time, who does not have the dignity they deserve, since the spotlight is cast on the last person who should speak,’ says Obasuyi.

Obasuyi has first-hand experience with the Italian media. In fact, at the time of the Macerata attack, she was invited to speak on a public broadcast talk show, an experience she remembers negatively. On talk shows, one of the most popular formats in Italy, POC’s presence is usually relegated to tokenism.

‘TV programmes are not suitable for deconstructing complex issues, especially when you invite someone from a far-right party to act as a counterpoint, without really listening but more to confirm your own prejudices and stereotypes about a whole range of people,’ she tells Media Diversity Institute.

Despite the international coverage the case received, a racial motivation may be difficult to prove under Italian law. ‘Systemic racism’, however, is far from a catchphrase. Actually, one piece of news related to the murder of Alika Ogorchukwu that was underreported concerns the difficulties in holding the funeral. So far, it has been postponed by several weeks; initially Alika Ogorchukwu’s brothers who live in Nigeria were having problems with the permits to get to Italy. Although they have now obtained visas, they currently face issues with the Consulate, however, Alika Ogorchukwu’s funeral is to take place in September. Laws do not only shape people’s lives but also their death, and the right of those left behind to process it. And, speaking about ‘systemic’ issues, the news cycle obeys the need to continuously produce content, not the need to understand and show the whole picture.

Photo Credits: Joe Matrix / Shutterstock