By Saba Chaudhury

@SaBa_Ch

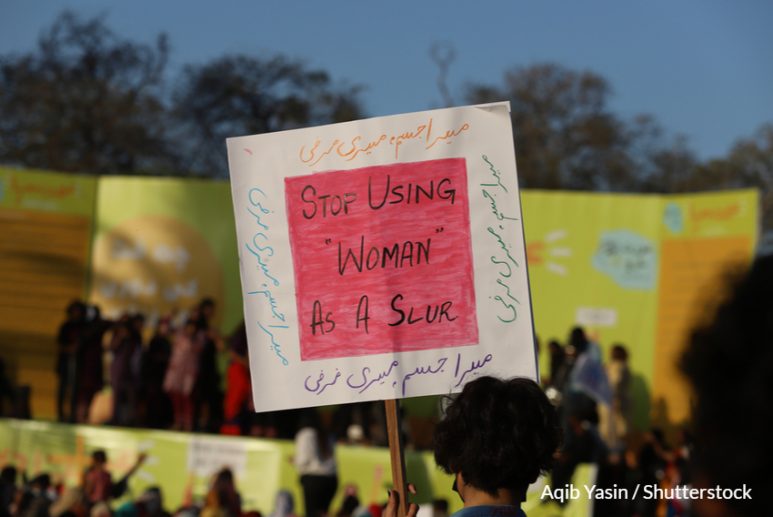

March 8 marks International Women’s Day, which is celebrated on that day in almost every region in the world. For Pakistan, International Women’s Day started being celebrated only five years ago with the name ‘Aurat March’. The importance of Aurat March for a country like Pakistan is significant, as the country currently ranks 153rd in the global gender index. It is a country where women, non-binary people and the trans community suffer from daily inequality and discrimination. Thus, the participation at a socio-political demonstration such as Aurat March is vital. It all started with a single message, however, what followed surprised the organizers as they never expected a large turnout year in and year out. However, despite the march’s popularity, the day is usually marked by negative comments, hate speech and backlash from the media.

This year, the backlash started long before the actual march. Hashtags such as #banMarch, #ForeignFoundedMarch #ShamefullMarch #againstreligion, #StupidMarch #FeministsAgenda, #WesternAgenda have been trending all over social media. Those who oppose the march tweet hateful narratives regularly under their online disguise in order to discredit the march. Fake social media profiles and online trolls take part in a relentless hate campaigns.

Traditional media’s role in enabling these hate campaigns cannot be ignored. When reporting on Aurat March, Pakistani media tend to discredit the march and its organisers. According to Asra Haque who reported on last year’s Aurat March in Lahore, male reporters from traditional media outlets who were covering the march “had heckled and hounded women protesters by asking provocative questions”. At the same time, while reporting on the march, journalists highlighted some of the women who took part at the march which led to online attacks.

In order to add some context, it is important to note that Pakistan is a rather patriarchal society and the media scene is not different. According to the global report by the International Women’s Media Foundation which took a sample from ten media companies in the country:

“Approximately, 3,200 people serve in the journalistic workforce of these companies, including 362 women and 2,842 men. Men outnumber women nearly 5:1.”

At the same time:

“Pakistani news companies surveyed do not demonstrate strong initiatives to adopt policies favorable to women in their workplaces”.

Reluctance to adopt gender policies in the workplace could be reflective of the way that the media report on women’s issues. In order to put this into a global perspective it is worth highlighting research done by UN Women and the Beijing Platform for Action:

“Research spanning more than 100 countries found that 46 per cent of news stories, in print and on radio and television, uphold gender stereotypes. Only 6 per cent highlight gender equality. Behind the scenes, men still occupy 73 per cent of top media management positions, according to another global study spanning 522 news media organizations. While women represent half of the world’s population, less than one third of all speaking characters in film are female. Cyber violence has extended the harassment and stalking of women and girls to the online world.”

“I feel that the media, like other institutions, is male-dominated. That’s why men focus on the slogans they think are anti-culture. Last year I was shocked when they tried to frame women’s March Lahore people for blasphemy, ” Muna Khayal Khattak, lecturer at the Department of International Relations at Bahauddin Zakariya University tells Media Diversity Institute.

In Pakistan, Women’s resistance has always been portrayed negatively by social and electronic media.

“The doctored image was another attempt to defame the march among common people. The electronic media is hellish – they invite cis men and paint them as heros. On social media the situation is even worse. Doctored images, twisted interpretations, edited and dubbed over videos are made. These people put in so much time and effort to defame the march if they could only do the same to try to understand it. They have extreme misconceptions about the march,” Khayal Khattak adds.

“In Pakistan, only a few male allies support the March and talk about women’s issues seriously. Unfortunately, many women also oppose the March by saying they never faced such issues. The privilege of not facing what underprivileged women face makes them criticize the March. Even privileged women need to unlearn these things in the first place. Women’s March in Pakistan is not anti-men but whole agenda portrayed by media is anti-March,” Sasha Javed, a journalist with over six years’ experience in electronic media tells Media Diversity Institute.

In developing countries, women’s movements are portrayed in a fun manner or as pranks. Even some of those who participate in Aurat March also don’t know the purpose, pattern and points of March. The posters and placards usually draw wide attention from conservative and religious people who criticise the march.

Fariha Anwar works as Senior Manager in an education-focused NGO.

“The media coverage of women’s March leans towards confirmation of pre-existing biases rather than any real attempt to educate the public on March’s charter of demands. Media’s thirst to sensationalize every issue has resulted in perception of this movement as a challenge to our cultural and religious values, instead of the legitimate human rights movement that it actually is,” she tells Media Diversity Institute.

“The electronic media coverage is particularly one-sided and relies on provoking outrage on selective, out-of-context slogans. Social media provides more autonomy to March supporters to put forth their stance, and they use it actively too, but the senseless criticism, trolling, and threats by the March critics again try to drown out these voices” she continues.

Fariha Anwar points out that constructive criticism is important for every movement but in a country like Pakistan there is no space for something like this as people would jump the bandwagon of misinformation without even making an effort to read the manifesto of the March.

“No one and no movement is perfect. And constructive criticism to improve the March and make it more relatable and acceptable to the masses should always be welcome. But that criticism would only be possible if the critics are willing to listen and ponder instead of acting all trigger-happy every time” Anwar concludes.

Photo Credits: Aqib Yasin / Shutterstock