By: Sophie Chauvet

A year ago, 12,000 purple-clad French women took the streets of Paris in the biggest march against sexism that the country had ever seen. Only a few streets away, 8,000 Yellow Vests were also marching. While most of the media was busy covering the controversial working class movement, the women only got two minutes of coverage on French national broadcasters. Yet it didn’t change the facts that on average, 219,000 women per year report domestic violence to the French police. In 2018, 121 women were killed by their current partner or ex partner. How could this sustained violence, and its protest against it, have been so invisible?

One year later, things are changing. The streets of Paris now showcase graffiti denouncing femicides. On November 23rd 2019, 49.000 Parisians, out-of-towners, and celebrities took the streets again—and this time, the national media is finally giving them the airtime they deserve.

How did the activists change their tactics, and what can we learn about how to use media to bring sexual violence out of the shadows?

Covering Domestic Violence: Sensational Headlines, Invisible Victims

Many French journalists are discussing the issue of women’s representation in the French media—particularly after the #MeToo movement and #LigueDuLOL scandal. However, until recently, there have been no accurate analyses of the scale of domestic violence.

Instead, domestic violence is covered in a lazy, insensitive that is almost always detrimental to survivors and lucrative to media moguls trying to sell sensationalist headlines. First off, domestic violence stories are categorized as “news briefs,” alongside serial killers, freak accidents and other one-off events.This lends itself to sensationalized headlines, baiting the reader’s voyeurism to drive clicks and sales, with little respect to survivors.

Another common mistake is focussing on the assailant’s rationale for perpetrating violence against his partner, usually put forward during a trial, where journalists often forget to ask the victim any questions, resulting in such headlines:“He strangles his wife because the dinner is not ready”, «She struggles with the crosswords, he electrocutes her», or «He hits her because there are lumps in his purée» . When the victim is not blamed altogether, media angles result in stories about a «crime of passion», or «family drama», further obscuring the event, and refusing to call it what it is: femicide.

Missing the target: When the Other Is To Blame

What is more, domestic violence is presented in the media as a crime that is horrendous yet exceptional. This is simply false; domestic abuse is the most common form of violence against women, and it is most often perpetrated by close acquaintances. And to think that it only happens to others contains another trap: that the others are underprivileged and/or immigrants, which plays into the far right narrative that actively associates immigrants with sexual violence.

Journalists who fall for this show their own bias; many French journalists come from white, secular backgrounds—something that shows in media coverage of immigrant communities and communities of color. Incidentally, they rarely examine cases of domestic violence from their own milieu.

Naming Matters: Taking Femicide Out of the Private Sphere

As these examples show, journalistic bias shows half truths at best, and dismiss violence crimes against women at worst. Feminist activists have been fighting against these narratives for several years now; now the fight has turned to how the media names—or doesn’t name—femicide.

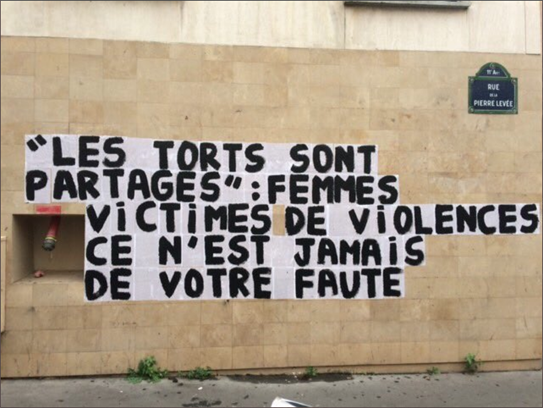

Diana Russell coined the term “femicide” in 1976, but people outside of feminist circles have still been reluctant to use it to refer to exactly what it means: the death of women, because they are women. Still, feminist associations are working relentlessly to publicise the term—and are starting to see results. Since the first campaign to publicize the term femicide in 2014, the movement has gained traction and visibility, with multiple organizations calling for a government response to sexist violence. In October, the activist group FEMEN walked bare chested with the names of the victims of femicides. Activist collectives like the Collage Féminicides have pasted messages denouncing femicides throughout the streets of Paris, bringing the idea from inside the home to the public sphere.

Many of these groups are becoming influential online, as well. The Féminicides par (ex) compagnons account has counted and documented every single women who died because intimate partner violence over the past year. Similarly, the #NousToutes collective counted the victims of domestic violence, and managed to significantly increase exposure of this issue in the media in creative ways. Every day before the November protest, they sent out emails and WhatsApp messages to more than 5,000 followers reminding them to publish a few posts on social media each day. The collective now counts more than 110k followers on Instagram, and is highly popular among young people.

The Results: A Public Outcry

Thousands of social media posts, meetings, flyers and protests later, even the mainstream media is starting to catch on. The Conseil Supérieur de l’Audiovisuel, France’s media regulator, has called on radio, TV, print and digital outlets to commit to promoting the coverage of sexual and domestic violence. According to the AFP, citations linked to violence against women have, since 2014, increased by 190 percent. The word «femicide» started replacing the problematic «crime of passion», and major national media outlets, such as Le Monde and Libération, have now covered the issue by putting several journalists on the beat. Perhaps most importantly, the AFP, which is where most news outlets get their content, has taken on the work of the Féminicides par (ex) compagnons collective and is investigating the issue further to provide more context.

At long last, could this be a victory for women in France?