By Dr Marcia Allison

The joint Channel 4, Times, and Sunday Times investigation in which five women have accused an English comedian Russell Brand of committing rape and sexual assault has once again brought the Me Too movement to the forefront of public conversation. First revealed in a Saturday night Dispatches special in which Brand’s behaviour was reportedly an “open-secret” on the comedy circuit, the detailed revelations of Brand’s self-appointed sexual Lothario status echoes the charges against Harvey Weinstein which made the Me Too movement into an overnight global sensation. Six years later, Me Too once again is trending as public figures such as Brand and GB News presenter Lawrence Fox was suspended and Dan Wootton was fired from MailOnline for Fox’s sexually demeaning and misogynistic comments against journalist Ava Evans. With six years of Me Too stories, we can begin to identify the patterns of and cycles of media reporting on the Me Too movement and sexual assault more broadly over the last half a decade.

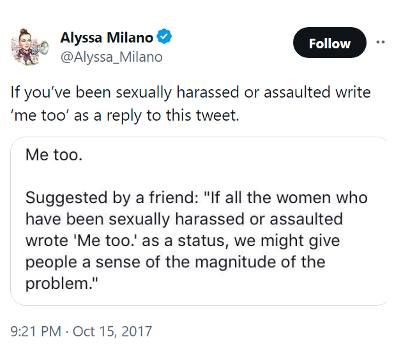

The Me Too movement was an overnight sensation that began when Alyssa Milano took to Twitter on the 15th October in 2017, just 10 days after the New York Times Weinstein allegations were released. Asking her followers to reply with the hashtag #MeToo if they had ever been sexually assaulted or harassed, in the following 24 hours over 12 million users responded, thus turning #MeToo into a defining moment for 21st century feminism. From spin-off hashtags to changes in law, the movement saw coverage of sexual assault (including Me Too reporting) grow by 52% in less than a year in the US. Conversely, in the UK, a 2019 Brunel University study led by Dr Sara De Benedictis found that 56% of Me Too media coverage was overtly positive, with the surprising finding that the traditionally anti-woke Daily Mail encompassed 31% of the total positive coverage of the movement. Here, with only 15% of Me Too media coverage taking an overtly negative view, it appeared a tide was turning in which De Benedictis found it was newspapers over social media platforms that were predominately bringing the Me Too concept to audiences beyond left-leaning social media users.

Whilst the increase in positive reporting on sexual assault and Me Too is a welcome development, such power to shape public understanding on the subject has significant consequences. With UK media outlets having notable ideological-biases and profits to be made in fueling the “outrage economy”, the public are not necessarily receiving the objective reporting that either left or right leaning institutions claim to offer. For instance, despite the overall positive reception of the movement, academics from the University of Melbourne have reported the continued use of problematic stereotypes that repeat victim-blaming and other misogynistic tropes that often defy reporting guidelines. Findings from Dr Karen Boyle that the media portray sexual predators as the exception rather than the norm fails to align with the 2019 Home Office figures that 20% of women and 4% of men above 16 have been sexually assaulted in the UK: a figure that infers a far deeper culture of sexual assault rather than the result of the aberrant individual. Moreover, even when left-wing papers such as The Guardian and The Independent offer their expected endorsement, De Benedictis notes how it has gone so far as to fail to offer any critiques of the movement, such as its predominate focus on white women as the victims of sexual assault.

With these indicators of bias in the positive reception to the movement, these become further pronounced in the negative reception to Me Too from Weinstein to today. Here, the same critiques continue to proliferate from ideologically-conservative and populist talking points. Rather than directly victim blaming, populist outlets fuel the outrage economy by deriding the ethos of the accuser as attempting to circumvent democratic processes through the “court of public opinion” and decry cancel culture as a failure of wokeness, despite the catastrophically low rates of sexual assault convictions. Moreover, right-leaning Me Too coverage has taken to framing the exceptional cases of false allegations as commonplace, and centre the danger of the movement to male lives in terms of their reputation. For instance, Stanford swimmer Brock Turner received just six months in jail for raping an unconscious woman as the judge feared that prison would have a “severe impact on him”.

Although it is still too early to replicate previous studies examining the first year of Me Too media coverage in 2023, initial observations show that whilst in print the media has distanced itself from Brand and has curbed overt victim blaming, sensationalist and controversial talking points appear to have been outsourced to video content in which clicks and engagement drives profits. For instance, The Sun’s championed pundit Piers Morgan revels in playing devil’s advocate on the subject on his TalkTV programme Uncensored by using predominantly conservative female guests to propagate misogynistic commentary. But with female-only panels only appearing for stories that focus on women’s issues, misogyny continues to be propagated when it drives profits through the outrage economy.

Altogether, the media reporting of the Me Too movement is a highly ideological enterprise that has yet to engage in the necessary introspection to understand its own complicit role and its profiteering from an ever-growing misogynistic culture. With sexual violence as an economic boon, Channel 4 also continues to profit from Brand: from its 2000s endorsement of his overtly sexual behaviour as cutting edge comedy, to the viewing figures and number of clicks regarding their Dispatches investigation. Moreover, outlets deriding the involvement of the media as opposed to the police itself is a highly hypocritical money making exercise. Altogether, such media reporting continues to support a situation in which it is not just sexual predators but misogynistic ideology that does not hide but thrives in plain sight.