By Iris Pase

February 6th is the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). Introduced by the United Nations in 2003, it is part of their effort in ending this harmful health practice. According to the World Health Organisation, female genital mutilation can be described as “the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” The practice doesn’t have any health benefits for girls and young women. It is actually recognised as a violation of human rights on an international level.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject, journalists are tasked with the tricky job of finding the best balance between accurate reporting and avoiding triggering trauma in their readers.

Unfortunately, mainstream media coverage often falls into sensationalist or downright judgemental narratives, usually “othering” the communities that are still affected by FGM, especially when they’re based in the UK.

Journalists and editors can play a fundamental role in overcoming the stigma and shame attached to FGM, fostering communication between communities and activists, and encouraging women to seek help when needed.

MDI asked a few FGM experts to share their advice for anyone reporting on the subject.

Accuracy Is Key

The internationally agreed term for this practice is “female genital mutilation”. Inaccurate terms like “circumcision” or overly specific terms like “infibulation” are best avoided when referring to the phenomenon as a whole.

Judgemental Language Can Only Cause Harm

“We need to use neutral language,” says Naana Otoo-Oyortey, Executive Director of British organisation FORWARD, which is led by African women working to end violence against women and girls. She adds: ”The worst part about media coverage is the language used in the news when referring to FGM. Words like ‘barbaric’, ‘degrading’ or calling people ‘archaic’.”

Otoo-Oyortey stresses how this language others the communities affected by FGM while also building a “hierarchy” of human rights violations depending on their area of origin. “FGM is harmful, it is an abuse, we know all these things,” she says. “It’s a continuum of abuse, just like domestic violence. However, FGM is treated differently from all other forms of abuse.”

It’s Gendered, Not Cultural

Stigmatising news coverage portrays FGM practices as a cultural issue stemming from different traditions, often insinuating they’re “less developed” than those from Western countries. This narrative is particularly damaging as it erases the gendered nature of this kind of violence.

As explained by End FGM European Network, FGM is only one of the many practices performed to control women’s bodies and roles in society.

Not Victims, Nor Survivors

People who have been affected by FGM should not be described as victims as it’s a stigmatising term which also takes their agency away from them.

We should also be careful in using the word survivor, Otoo-Oyortey tells the Media Diversity Institute. “Sometimes people are called a survivor of violence because they’ve come out of it,” she says. “For me, a survivor is somebody who has gone through a traumatic experience and has come out strong. However, not everybody does.”

This is the reason why FORWARD prefers using the terms “affected communities”, “people who have gone through FGM” or “women who have experienced FGM”. Otoo-Oyortey adds: “Sometimes you can be affected and not necessarily be seen as a victim or survivor, you’ve just been affected in one way or the other.”

Educate Yourself

Especially given the sensitive nature of the topic, it’s important that reporters do the required research to deliver accurate and reliable news.

Adequate preparation will avoid you making dangerous mistakes such as framing FGM as a practice that is performed only by a particular religious group or geographical area. It will give you a broader spectrum of the reality of this practice and the people behind it, which should be at the forefront of your reporting.

Having more knowledge will also help you connect with your interviewees and make them feel comfortable speaking to you. This is particularly true when dealing with marginalised communities, especially when they have been extensively misrepresented by the media.

Tell Positive Stories Too

FGM is not practiced out of nowhere, it is a phenomenon affecting several countries and people from different backgrounds. Learning who and where they are can significantly change (for the better) the media reporting of FGM.

“There are many charities that, like us, have done a huge amount of work in terms of community engagement”, Lena El-Hindi, Community Outreach Director of British charity Oxford Against Cutting, tells the Media Diversity Institute.

“We work with the communities, with the men, with the grandmothers. That needs to be covered along what is happening with the youth,” she adds.

FGM is more than the practise itself, it is rooted in a social context which pressures women into going through the practice for a variety of reasons that need to be comprehended when reporting on the subject. “FGM is related to a lot of things you know,” El-Hindi continues, “if you look at it, it is related to economic aspects, marriage abilities, sex and sexuality. It can’t be pinned down to simplistic narratives.”

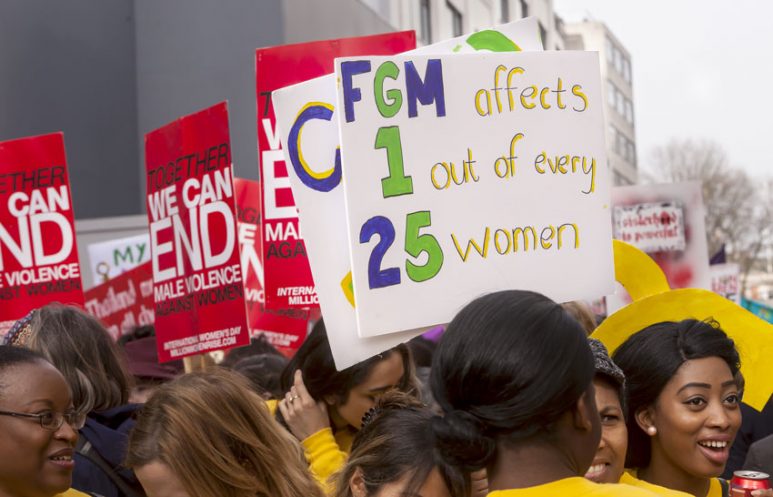

Use Positive Pictures

Journalists should work with the picture desk to ensure that traumatising or graphic images are not published. Photos or illustrations of blades or blood, for example, are shocking images that risk causing people who experienced FGM to relive their trauma.

El-Hindi says: “I think my community would be happy to see a picture of themselves, maybe of when they’re gathered in an FGM event or talk. I don’t see that quite often actually.”

Pictures play an important part in changing the narrative around FGM which, at the moment, is often tragic and sensationalistic. She adds: “You don’t actually see pictures of communities, or young people or men who are actually trying to make a change. You don’t see pictures of children, maybe talking about the effects of FGM. You always see pictures of victims.”

Reporting about female genital mutilation can surely be tricky but hopefully, these tips will lead you in the right direction. If you’re looking for more information, you can look at the useful resources offered by Oxford against Cutting and FORWARD UK. In addition, further guidelines on respectful reporting on FGM can be found on the End FGM European Network’s website.

Photo Credits: Ms Jane Campbell / Shutterstock