By David Tuller*

This essay is from the upcoming book to mark the Media Diversity Institute’s 25th anniversary. The book consists of essays by academics, journalists, media experts, civil society activists, and policymakers – all those who have supported us in our work towards diversity, inclusion, and fairer representation of marginalised and vulnerable communities in the media. The paper version of the book will be launched at the Anniversary celebration on the 17th of November 2023 in London. Watch this space for the other 24 essays.

In the fall of 1994, I was living in Moscow and gathering material for what eventually became a book called Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels in Gay and Lesbian Russia. With my friend Ksusha, I attended a three-day “les-bi-gay” workshop conducted by three American activists. This was their third visit to Russia for the purpose of engaging in “community building,” they told the dozens of us gathered.

The phrase immediately triggered my cynical skepticism; everyone from the West seemed to be engaged in some kind of “building” activity in Russia. Mormons and Jesus-lovers were “building religion.” Business consultants were “building capitalism.” There were no end of Americans involved in “democracy building.” Many of these efforts struck me as inappropriate, naïve in the extreme, pathetically ineffective. The les-bi-gay community building effort seemed no different.

The first session, on Friday evening, drew about 50 people to a stuffy basement in an outlying Moscow district. The three Americans droned on and on about identity politics, self-love, coming out, group process, and yada yada yada. They lost the audience quickly. The participants giggled at random moments and seemed a bit bewildered by the goings-on. By the third session on Sunday, only about 15 attendees remained in the les-bi-gay seminar.

A couple of days later, I met with two of the American seminar leaders to discuss their work. An American friend of mine, Laurie, a sociology grad student gathering material for her doctorate on gender issues in Russia, accompanied me. Alma, one of the seminar leaders, told us that they’d engaged in an invaluable “needs assessment” before the seminar. They had learned, she said, all about the coercive Soviet method of ideological indoctrination.

“You really should check that out!” she advised us enthusiastically. “There’s been a lot of dysfunctional group behavior that causes people to have a lot of shit and pain around groups and leadership!”

Laurie and I glanced at each other. These people were engaged in “community building” here, and had just realized that Russians had “a lot of shit and pain” around groups? Had they heard of Stalin?

A few days later, I was hanging out with Ksusha and our friend Sveta. Ksusha began ranting about the ridiculousness of the whole enterprise.

“Really, Sveta, it was like kindergarten, just like kindergarten,” she said. “Imagine telling Russians that they have to be in some stuffy basement room at 10 am on the weekend and stay for ten hours, when they could be at the beach! Maybe if these Americans had held it in the woods or somewhere outside…”

She leaned toward me, waved her arms, and launched into a diatribe against “collectives.” “David, we were always in collectives, in groups—at work we’d gather once a week, once a month for. Ideology lectures. Russians hate that. What do we need it for? Maybe Americans need that, but we don’t. We need places to meet—bars, cafes, discos. Just to meet, to see each other. Maybe after we have these places for a while then we’ll want to gather in groups and talk about ourselves.”

Sveta seized the opportunity to have the last word. “Well, Americans think they can save us,” she chortled. “They think that they’re the Messiah. Or Superman. And as for the American gays and lesbianki, they think they are the Supergays and the Superlesbianki!”

I couldn’t disagree with her analysis.

**********

This and related experiences during the time I lived in Moscow served me well when I became involved in the journalism training world. In 1998, after almost a decade as a reporter and editor at the SF Chronicle, I received a fellowship from the Knight Foundation to spend nine months in St Petersburg. I would be working with a new media diversity program being created by Milica Pesic, a Serbian journalist living in London, under the auspices of New York University’s Center for War, Peace, and the News Media. I’d taught some undergraduate journalism courses in San Francisco, and obviously I’d lived in Russia, but beyond that I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to be doing or how I was supposed to do it.

I was very aware that the countries scattered across the post-Soviet landscape were teeming with US and Western advisors in all spheres of activity—banking, public health, legal systems. Perhaps some of these efforts were useful, but others were infused with undeniably imperialistic impulses. In my travels, I had recognized the extent to which this overbearing approach had been pursued even in the domain of gay and lesbian rights. (In those days, no one would have understood “LGBTQ”!) I didn’t want to repeat the pattern in journalism. I tried to approach the work with caution and humility.

Milica and I bonded during our first trip together—two weeks in Albania in February of 1998. She impressed me with her charisma, her humor, her boundless energy, and her dedication to her work. During these first workshops, I generally followed her lead until I gradually got my footing. Later that year, we traveled together to a media diversity gathering in Ohrid, Macedonia. In 2003, we conducted nine days of training in Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan–the three former Soviet Caucasus republics. I also wrote some reporting diversity training materials for MDI, which were then translated into multiple languages.

Milica took our responsibilities seriously but also loved turning everything into an adventure. In Georgia, we decided—with the approval of the participants–to move the workshop from Tbilisi, the capital, to the ski resort in the mountains. We skied during the day and held our seminars in the evenings. That worked out great for everyone. In Baku, when I saw a beautiful red antique carpet in the market, I returned later in the day with Milica, who gave a brilliant performance as my financially savvy wife. The sellers understood quickly that she controlled the family budget. They smiled at me knowingly and immediately agreed to lower the price. (That red carpet still graces my living room floor in San Francisco. When I look at it, I smile and think of Milica.)

I worked as well for other journalism training programs sponsored by either US or European funders. When accepting these assignments, I always sought to work alongside local trainers, who had a more pragmatic and realistic take on what was feasible for the journalists in our groups. They were obviously much more familiar with the facts on the ground—what was feasible in terms of reporting strategies, and what was not. I could offer suggestions or ideas, but I accepted that some would be dismissed as irrelevant or as impossible to execute, for whatever reason, and that some participants would likely reject everything I said just because I was American.

I also recognized that journalists in the post-Soviet and former Eastern bloc countries, including workshop participants, often maintained financial arrangements with advertisers. Some American trainers expressed shock at learning that journalists sometimes wrote ad copy for money—even as they covered news stories about the advertisers paying them. Or they engaged in other actions that would be grounds for immediate firing in the U.S. I didn’t share the outrage I saw some of my compatriots expressed. I was aware that our local colleagues lived in their reality, not mine. They had to feed their children, not me. So they had to make the decisions they needed to make in order to survive. I couldn’t judge their choices.

**********

In any event, I was a bit hesitant when Milica asked me to review and edit the essays for this book. Editing is often a thankless job. Most people are understandably sensitive about having their writing assessed—I certainly am. And not surprisingly, journalists generally pride themselves on their ability to communicate; in my experience, they don’t always take kindly to rigorous editing. Taking on the task of dealing with dozens of essays about controversial issues involving diversity and the use and misuse of media and language seemed like a daunting prospect fraught with pitfalls and possibilities for conflict.

Moreover, most of the authors were not writing in their native languages but in English. I speak two other languages—Russian and French. But while my spoken fluency is pretty good, I am very aware that I am incapable of writing a serious paper in either language. I dread to think of someone having to edit whatever I would come up with.

I assumed that many or most of the authors would be translating in their heads as they were composing their articles. Words and phrases in translation, even when technically accurate, do not necessarily carry the same valence as in the original language. Sometimes the translated word is more powerful and aggressive than in the original, sometimes less so. Shades and nuances of meaning can also get lost. This certainly happens with slurs, whether they involve race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, citizenship status, or other demographic categories. They can be translated, of course, but they resonate differently—the weight of the opprobrium they carry does not necessarily come across, or it comes across with even greater force.

Would corrections I might make to awkward phrasing be accepted as offered, as well-meaning suggestions from a journalism colleague? Or would they be viewed with concern and suspicion, coming as they did from a white American guy in his 60s? I didn’t know. (I suppose I get exemptions for being gay and Jewish, but I think my point is clear.) I was concerned that suggestions or changes made for linguistic or grammatical reasons related to English usage or style would or could be misinterpreted as efforts to censor or silence.

I fretted about all these things before accepting the job. But I figured someone was ultimately going to have to edit the essays, so it might as well be me.

In each case, I did my best to retain the writer’s voice even as I fiddled with some of the phrasing or suggested trims or asked questions about various references or statements. Some of my responses undoubtedly arose out of my limited awareness and understanding of particular local contexts, historical events, and regional trends. But as an editor I tend to be nit-picky and detail-oriented. If I find myself confused or lost, I assume some other readers might as well, so I always feel it is my responsibility to alert the authors. The trick is in being able to broach every issue with care and sensitivity while remaining alert to the possibility of offense arising from linguistic misunderstandings.

I hope that, for the most part, I was able to perform this task respectfully, and that no one felt my edits were designed or intended to undermine or deflate the meaning they wanted to convey. My goal in all cases was to try to help them get their points across as clearly as possible—not to distort their message or impose my own ideas or thoughts or political viewpoint. I really enjoyed the exchanges I had with some of the authors via the comment bubbles on Word documents, often extending through two and three revisions.

That’s a long way of saying that editing these essays was a challenging job! But it was definitely a rewarding one.

As I read these powerful, heartfelt, and probing accounts, I was surprised at how much I learned. For one thing, they provided me with a window, or multiple windows, onto MDI’s history. I knew bits and pieces from what Milica had said and what I’d picked up during my own involvement with the organization. But given the diversity and range of the essays, reading them helped fill in many of the pieces. I hadn’t realized, for example, that MDI started off working only with reporters and then expanded to include media owners and decision-makers. Later on, I learned, Milica recognized the importance of working with non-governmental organizations that represented disadvantaged groups and ethnic minorities, training them on how to get the word out and reach media organizations with their messaging, as well as with academic institutions seeking to develop curricula and programs on media and diversity.

In fact, before I accepted this assignment, I was actually unaware of the vast reach of MDI’s efforts, especially in the last 10 or 15 years. After working on the MDI training manuals years ago, I had devoted most of my time to study and then work at the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. Milica and I maintained our friendship, but I had little ongoing professional relationship with MDI. So in reviewing the essays, I was blown away by how many programs MDI had sponsored in far-flung regions, how many local journalists it had impacted, and how many initiatives it had pursued. I was impressed all over again by Milica’s energy and vision as well as her ability to bring together media professionals from everywhere to discuss and debate these critical issues.

I was also immensely moved by the passion expressed by all the authors, no matter their perspectives, as well as their shared commitment to the notion that journalism and all forms of media can and must be used as tools for positive change. Many of the authors grew up in extremely harsh and oppressive circumstances, yet they have managed to retain their humor, their humanity, and their desire to promote inclusion, tolerance and diversity. I find myself immensely inspired by this resilience.

In other words, despite my initial trepidation about taking on the project, in the end I felt humbled, honored and touched to review these brief but revealing glimpses into MDI’s past and present and into the lives of people invested in its core mission. I hope, and expect, that the essays will provoke a similar range of reactions among this book’s readers.

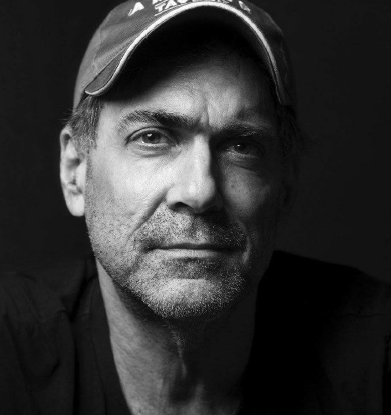

*David Tuller, DrPH, is Senior Fellow in Public Health and Journalism at the Center for Global Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. He received a masters degree in public health in 2006 and a doctor of public health degree in 2013, both from Berkeley. He was a reporter and editor for ten years at The San Francisco Chronicle and served as health editor at Salon.com. He has written regularly about public health and medical issues for The New York Times, the policy journal Health Affairs, and many other publications.