By Sümeyra Tansel

“The native speakers of Ladino are now around 80 years old. When we lose them, there will be no one speaking this language as their mother tongue,” says Karen Gerson Şarhon, the editor-in-chief of “El Amanaser”, the only newspaper in the world written entirely in the Ladino language.

Ladino, also known as Judeo-Spanish, is a minority language mostly spoken by Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire, whose current population is estimated at 150,000 globally. The language derives from Old Spanish dialects, and their mixture gave birth to it in the Ottoman Empire when the Jewish population of Spain was exiled in 1492. Today it is spoken mostly in Israel and Turkey by Sephardic Jews and has been recognised as a minority language in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Israel, France and Turkey.

Karen Gerson Şarhon (63) has devoted herself to keeping Ladino alive. She learned the language from her family.

“Until my generation, Ladino was part of our ethnic identity. The language of the Jews in Turkey was Ladino. After my generation, that disappeared because we don’t speak Ladino at home,” says Gerson Şarhon.

In 1492, the Sephadic Jews settled in Turkey. The Ottoman Empire allowed Jewish people (and all minorities) to speak their own language in public but after the fall of the Empire, modern Turkey in the 1920s followed a stricter language policy which wanted citizens to speak only Turkish in public places.

“Jewish people thought that if they talked Ladino with children at home, they would not learn Turkish well and they would be discriminated against. Then they started to speak Turkish and Ladino started to decline,” says Gerson Şarhon.

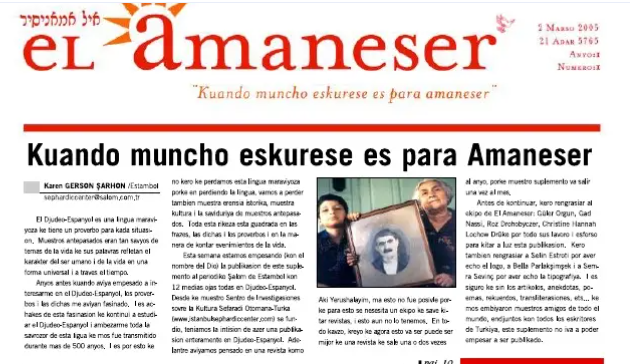

In 2003, Şarhon founded the “Ottoman Turkish Sephardic Culture Research Center” in Istanbul. In 2005, with the help of Şalom, the only newspaper of the Turkish Jewish community, she created El Amaneser, which means ‘Dawn’. El Amaneser is the only newspaper in the world written entirely in Ladino and its purpose is to keep the language alive.

“In the beginning, we were afraid that we would not find enough material to publish in the newspaper, but we never had such a problem during these 17 years. We are getting articles from Sephardic people all over the world for us to publish” says Gerson Sarhon.

After 18 years of publishing El Amaneser is still being published monthly and celebrated its 200th issue last November. Today it consists of 32 pages.

“We cover a variety of topics, from health to history and current events. We want to show people that you can write about anything using Ladino. We have expert writers in their field who can write in Ladino,” says Gerson Şarhon.

Isak Eskinazi (83) and Anna Eskinazi (78) are a couple from the Turkish Jewish community. Although Ladino is Isak Eskinazi’s mother tongue as his family was speaking it, he is considered the last of his family to speak it.

“My children do not know Ladino. My wife and I speak Turkish with them. I grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in Istanbul, where everyone spoke Ladino. But today there is no such neighborhood in the city. Education is another challenge for Ladino. There is no education in this language, which makes it difficult to preserve it,” says Isak Eskinazi.

Anna Eskinazi is an Ashkenazi Jew whose mother tongue is Yiddish, however, she also speaks Ladino as she grew up in an Istanbul neighbourhood where Ladino was spoken.

“I learned Ladino from our neighbors. It was a natural process. I heard it and talked to them. My mother-in-law could speak good Greek because most of her neighbors were Greek. It is difficult to find people who speak Ladino or Greek in Istanbul today, ” Anna Eskinazi tells Media Diversity Institute.

Isak Eskinazi says that El Amaneser is vital for the preservation of his mother tongue.

“Reading newspapers reminds me of some words I forgot and I learn new words as well. It’s very enjoyable for me. There I see the language of my mother and father.”

Apart from the preseravtion of the language for those who already speak it, El Amaneser has also acted as an educational tool for those interested in learning Ladino. Kenan Cruz Çilli is a Turkish-Portuguese researcher. He is not Jewish, but he is interested in minorities and cultures in Turkey. He saw El Amaneser for the first time in the Jewish museum and realized that he could understand some words due to his knowledge of Portuguese.

“It was very interesting for me to understand some words. I did more research on the language. During the pandemic, I decided to learn it in depth. I can say that I learned the language from the newspaper, but my Portuguese background helped me a lot in this process. One day I decided to write a text in Ladino and send it to this publication. After a while Karen Şarhon came back to me, correcting my text. She told me that she wanted to publish my article in El Amaneser. So I became one of the writers of the newspaper. Now I speak Ladino fluently. People are surprised about how I learned a dying Jewish language although I am not Jewish. They said “Our grandchildren don’t show interest the Ladino but you learned it,” he tells Media Diversity Institute.

“It makes me very happy to see young people’s interest in the language,” says Gerson Şarhon.

“Kenan is such a big talent. I am impressed to see how he grasped everything quickly. He learned Ladino by reading Amaneser, ” she continues.

Even though the Sephardic community has been living in Turkey for centuries, a recent Netflix drama called ‘The Club’ raised interest in their culture among the Turkish population. The Club focuses on Turkey’s discriminatory policies against the Sephardic Jews during the 1950s.

“After the Club, interest in Ladino increased a lot. People had never heard of Ladino or Sephardic. It’s understandable as we are only 15 thousand as in a country of 83 million people,” says Gerson Şarhon.

However, she is not very optimistic about Ladino’s future as the interest in learning and perserving the language by younger generations is very low. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic and the consecutive lockdowns seem to have played a small part in changing those trends.

“A lot of young people reached us and said that they wanted to learn their grandparents’ language. They were from across the world. So I and other Ladino instructors from the USA organized online Ladino courses for many young people. They learned very well. I have recruited some talented ones who are in their 20s as writers for the newspaper. This big and sudden interest makes me so happy and gives me hope for the future of Ladino and the Sephardic culture,” Gerson Şarhon tells Media Diversity Institute with relief and a sense of optimism for the future of the language.

Photo Credit: Screenshot from Al Amanaser’s website