By: Safiya Ahmed

When Donald Trump insisted on calling the novel Coronavirus the “Chinese Virus” it was frighteningly reminiscent of the way that language around the AIDS epidemic stigmatized African diaspora and other Black communities for generations.

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, the discourse around the HIV virus obsessed over Africa as a “diseased continent.” It built on the existing racist tropes of Africa as a “dark continent” where danger lurks in every corner.

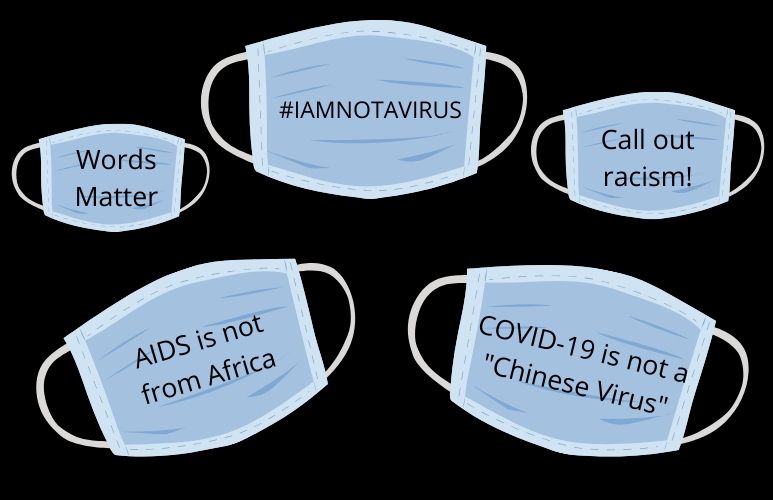

Now, the narrative surrounding Coronavirus is doing the same to people of Asian descent around the world. On social media, #YellowAlert and #ChineseVirus have “gone viral”—so to speak—and with it, the racism that they carry. After reports started coming in of increased hate crimes against Asian-American communities in the San Francisco Bay Area, the group Chinese for Affirmative Action started gathering testimonies of attacks and harassment. Within twenty-four hours of launching the tracker, they had logged more than forty incidents.

But the attacks go beyond the Chinese community. In fact, it reveals another troubling lack of understanding of the diversity among Asian communities in the west—that anyone, regardless of if they are Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese or even Laotian or Filipino is “oriental” or, in this case, “Chinese.” According to the testimonies, almost all Asian groups have been vilified.

It is reminiscent of the way that the AIDS epidemic cast the entire continent of Africa as disease ridden, without examining how the disease was actually spreading. It is a trope that continued to haunt Black and African communities through the Ebola crisis, where incidents happened such as Nigerian students being denied acceptance to universities over “Ebola” (even though Nigeria had no confirmed cases) and a Pennsylvania football player was met with chants of “Ebola” from the opposing team. More general racism, such as Trump’s insistence that many of these countries are “shitholes” only drives home these narratives as acceptable. In the same way that media narratives took the HIV virus’s origins with chimpanzees, and used it to mock Africans’ culinary habits, many are taking the possibility that the Coronavirus originated in a Wuhan seafood market and spinning it into a narrative that blames Chinese culinary culture.

Even though the World Health Organisation (WHO) called on scientists, national authorities and the media to use neutral language when naming new diseases—citing that names such as “Middle East respiratory syndrome” or “Swine Flu” had negative impacts on certain communities or economic industries—insisting on names like the Chinese virus or the Wuhan Flu directly contradict these guidelines. This kind of stigma has consequences; in South Africa, former President Thabo Mbeki refused anti-retroviral drugs, insisting that the virus was not impacting South Africans.

“The stigma associated with referring to an illness in a way that deliberately creates unconscious (or conscious) bias can keep people from getting care they may desperately need to get better and prevent others from getting sick,” Marietta Vazquez, a Professor of Pediatrics in Division of Infectious Diseases and General Pediatrics at the Yale School of Medicine told Media Diversity Institute.

“When faced with this type of constant, heightened discrimination our friends, neighbors and colleagues of Asian-decent can feel uncomfortable in places they should feel welcome, included, and safe. This type of discrimination may also put their mental health at risk”.

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) has published guidelines for journalists covering the Coronavirus Outbreak. It raises concerns about how news articles include images of Asian people wearing facemasks without providing context, including that facemasks are common in East Asian countries to protect against pollution—with the practice crossing over to immigrant Asian populations. They also object to the use of generic images of Chinatown unless directly related to a news story rather than to illustrate the virus—another topic that has been covered by Media Diversity Institute.

In its guidelines, the AAJA praised news outlets for covering the impact the virus had on the daily lives of Wuhan residents, for depicting the culture and history of Wuhan beyond its relation to the virus as well as the proliferation of xenophobic incidents against those of East Asian descent around the world.

There are parallels to the AIDS epidemic in the resistance as well. Around the world, social media users are encouraging people to support Chinese restaurants and businesses with hashtags like #DontDumptheDumplings and the resuscitated campaign #iwilleatwithyou, which was built in response to anti-Muslim racism. While the AIDS epidemic struck before social media, African diaspora populations around the world printed T-Shirts that said, “AIDS did not originate in Africa F&** What you Heard.”

It might not be possible to change the attitudes of those who wish to politicise the pandemic, but the media must double its efforts to uphold the WHO’s standards, and not platform the racism of others. It is only by coming together and standing in solidarity that we will be able to fight the virus, and the racism that comes with it.