by Varduhi Baylan

Turkey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan signed a decree at midnight on 19 March about the withdrawal of Turkey from the Istanbul Convention. This decision, made without any parliamentary debate and consultation with the civil society, is a withdrawal from the protection the convention provides against domestic violence and all acts of gender-based violence resulting or possibly resulting in physical, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to the victim. It is the first time in the history of Turkey that the country withdraws from a human rights convention.

The discussions of withdrawal date back several years. In July 2019, Saadet Party deputy Abdulkadir Karaduman labeled the Istanbul Convention as a monster ”written to bring down our family structure” calling for the annulment of the convention. Since then, the conservative political circles have expressed concerns that the Convention ‘‘threatened the family’’ over a misinterpretation of the term gender stated in the Convention. For about two years, conservative circles have targeted the 6284 Law that Protects Family and Prevents Violence against Women as well as the Istanbul Convention. The law and the convention were put on the target board and labeled as ”enemy of the family”, ”enemy of men”, ”family destroyer”, and more.

In an interview in 2020, former GREVIO President Prof. Feride Acar stated that Turkey set an important course of action about violence against women adding: ‘‘However, if it withdraws from the convention, it will waste all gains in that regard.’’

Despite the withdrawal from the convention, it is still valid till the final annulment on July the 1st. The reference for the 6284 Law adopted in 2012 was the Istanbul Convention, so it is still an assurance of the prevention of violence against women. However, has this withdrawal started affecting women’s rights negatively?

Political discourse shaping the actions of the practitioners

Feminist lawyer Deniz Bayram is sure that the political discourse and statements shape the implementation of the convention.

“If some political subjects and actors talk about certain issues in Turkey, it can be perceived as an instruction by the practitioners. And if there is a discourse on whether or not the Istanbul convention should be applied, the courts actually act on the basis of these political discourses instead of the legal documents stated in the law and the Convention. For example, the judges can give protection orders for a shorter period of time or they can even demand evidence when making a protection order,” says Bayram.

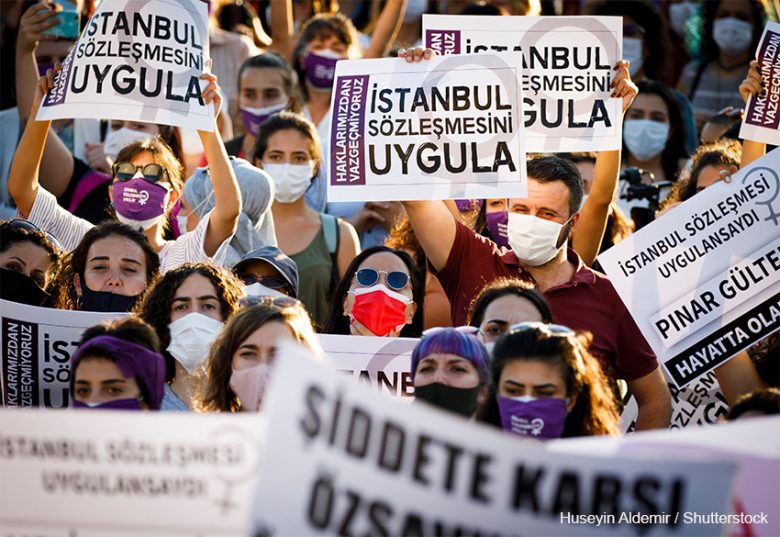

Since the day of the decree’s publication in the Official Gazette, the women’s movement and many women’s organizations have been organizing campaigns against withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention.

“There was not long enough time to make observations on the consequences of Istanbul Convention withdrawal, but there were already some problems and difficulties in its implementation from the beginning of the attacks against the Convention. Since the annulment decision, data from the field show that difficulties regarding protection decisions may arise,” explains Bayram.

Cases of ‘protection’ denial by the authorities’ approach as if this mechanism will no longer be applied became more common after the withdrawal.

“The application problems of the Convention articles were already at a serious level. Unfortunately, we can say that it is highly probable that these cases will increase further,” says Bayram.

The convention and article 17 not fully enforced

In 2017, bianet prepared a shadow report compiled from media coverage concerning male violence in Turkey from 2014-2016, as a response to GREVIO’s first period questionnaire. The report finds media approach to violence against women tolerant: “Mainstream media in Turkey has no ethical principles that consider social gender awareness and avoid using destructive gender patterns and disseminating images, which humiliate women as well as link violence to sex.”

The implementation of article 17 was never fully supported by the state as a party to the convention meaning it did not put much efforts “to participate in the elaboration and implementation of policies and to set guidelines and self‐regulatory standards to prevent violence against women and to enhance respect for their dignity.”

“In fact, the Istanbul Convention and the law 6284 aim at avoiding unequal representation of women in advertisements, TV shows, TV serials, and any visual broadcast, and avoid messages that will legitimize and romanticize violence against women. It imposes obligations to emphasize the gender equality, to stress the illegality of violence, the importance of the investigation in cases of violence against women. This is supposed to be achieved with various steps like a set of public advertisements, organizing awareness campaigns, etc” says Bayram.

According to her, one can barely speak positively about the perception of women in Turkish media. Even if there is awareness rising in the media regarding gender equality, it is not because the state as the party to the convention fulfills its obligations and takes the necessary steps, but because the feminist movement in Turkey is on the rise.

”The massive increase of feminism brings a more sensitive approach in some TV programs and serials. Various messages can be spread regarding gender equality or violence against women. Of course, it is impossible to call this sufficient,” Bayram continues.

The Ministry of Family and Social Policies (currently Ministry of Family and Social Services) did not prioritize the implementation of this article. There were various processes regarding administrative structuring. The General Directorate of Women, which was mainly responsible for the convention, weakened. Likewise, the preparation of guidelines, or the initiation of a campaign to combat violence against women foreseen by the Article 17 were not prioritized.

“Only in the first years when convention was enacted, public advertisements with a number of messages were made by the ministry. One cannot call this sufficient. If the law and convention were really enforced, we would be seeing truly comprehensive awareness raising campaigns in the media on combating violence against women,” Bayram tells MDI.

The aftermath of LGBTI+ reflection in the media

The perception that the withdrawal from the convention only affects and will affect women and will be a step back in preventing the violence against women excludes LGBTI+ movement which does not have any other real assurance rather than the Istanbul Convention in Turkey. There is no article in local legislation towards the protection of LGBTI+ rights. This as well concerns the aftermath of the media regarding LGBTI+ individuals.

There is a decline in the representation of women in the media. More and more problematic news appear in terms of gender equality, sexual orientation and respect for gender identity. Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) Chairman Ebubekir Şahin, in his statement to Akit on Netflix series Aşk 101, said: “We are determined not to allow immorality” directly targeting the LGBTI+ community. In December 2020, the Advertising Board within the Ministry of Commerce of Turkey decided that “LGBT and rainbow- themed products should be offered for sale on e-commerce sites with the phrase +18“. “Such decisions legitimize discrimination against LGBTI+ individuals, legitimize hate crimes.”

Having a legal document had the effect of compelling the administration, the media organizations, the private sector to comply with the obligations of the convention, and was providing a means of coercivity. And unfortunately, with the withdrawal, not only the legal tool providing coercion has disappeared, but also provided opportunities to further incite, encourage and legitimize hate crime against LGBTI+ individuals.

The withdrawal as a mean to silence the media

The final annulment of the Istanbul convention will leave no enforcement on media and private sector involvement foreseen by the Article 17; besides that it may become a mechanism to silence the media covering violence against women and/or LGBTI+ individuals.

“Although there are serious drawbacks in the implementation of the Convention, even though RTÜK continues to adopt conservative attitude, the withdrawal from the convention will be a serious blow to the independence of the media and freedom of expression. The annulment of the Istanbul Convention can also be used against a media organization that covers violence against women and can turn into a pressure mechanism,” says Bayram.

“The Istanbul convention is the basis for the media coverage towards awareness raising in various topics like; abduction of a woman, being subjected to violence by a member of a certain political group, being subjected to sexual assault, reporting about femicide cases, reporting on the lack of data on violence against women, as well as on the inefficiency of policies to combat violence against women,’’ she continues.

Deniz Bayram has concerns that such contents that are ‘not pleasant’ to conservative political circles may get targeted by those circles and legally

“Unfortunately, at the point we have reached, in this atmosphere, it is possible that these news will be blocked, censored or somehow certain policies will be produced towards media organizations that publish these news,” lawyer Deniz Bayram concludes.

Notes

The Istanbul Convention was opened for signature at the meeting of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe held in Istanbul on May 11, 2011. On March 12, 2012, Turkey became the first country to ratify the Convention, followed by 32 other countries from 2013 till now. The Convention came into force on 1 August 2014.

Deniz Bayram is a lawyer involved in feminist activism, part of the feminist movement in Turkey. In 2012, working at the Morçatı Women’s Shelter Foundation, Bayram was directly involved in the process of making of the 6284 Law. Currently, she works on the lawsuit examples of the foundation against the decree on withdrawal from the convention.

Photo Credir: Huseyin Aldemir / Shutterstock