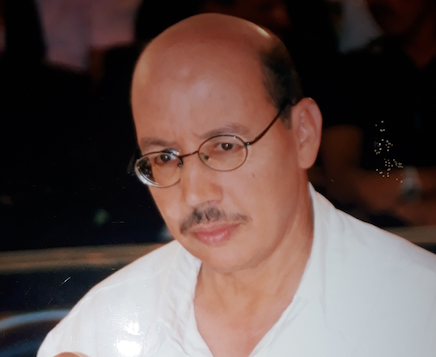

Safi Naciri*

This essay is from the upcoming book to mark the Media Diversity Institute’s 25th anniversary. The book consists of essays by academics, journalists, media experts, civil society activists, and policymakers – all those who have supported us in our work towards diversity, inclusion, and fairer representation of marginalised and vulnerable communities in the media. The paper version of the book will be launched at the Anniversary celebration on the 17th of November 2023 in London. Watch this space for the other 24 essays.

Salah is one of the guests I hosted on “Zaman Al-Haky” (The Storytelling Times), the talk show I hosted for years on Moroccan radio. The program hosted a significant segment of the elite, but my interview with Salah was different. Every time I listen to it, I burst into tears.

Salah was in his twenties when he was abducted, and he spent nearly nine years in secret detention alongside five comrades. They spent two years handcuffed and blindfolded. Then, suddenly one day at dawn, they were loaded onto a bus surrounded by soldiers on all sides. Perhaps they are on their way to be executed?! How could this be happening to teenagers for just distributing secret leaflets? The journey continued, and the hours passed until they finally arrived at another secret detention centre in the middle of nowhere in the desert. They were housed in dark cells that were closed all the time, during the freezing winters and scalding summers. It was like a corner in hell, where hunger, filth, diseases, and brutal beatings were their daily morning routine. They felt disconnected from place and time. They lost any contact with their families, who knew nothing about their whereabouts. Every passing day reinforced the feeling that they would die and be buried there without anyone knowing about them.

Salah told me all that, but he told much, much more as well. My words are powerless to describe the hellish torture that Salah and his comrades endured, the sadism of the executioners, who enjoyed torturing their victims. Language fails us miserably in such situations.

One morning, they were released. The young men couldn’t believe they were free. They were in a state of bewilderment. For months, they had difficulty believing they had been released. Upon his release, Salah was given a single banknote to arrange for his transportation from this remote point in the desert to the capital, and then to his family’s house.

He arrived in the capital at night; it was winter, and his spring clothes were unable to protect him from the bitter cold. It was too late at night to find any transportation. But Salah began to wonder in confusion, was his family still living in the same house? Nine years had passed. Was his mother still alive? What about his father? His siblings? He was afraid that if his mother opened the door and found him after these years, she might not be able to bear the shock and would be struck by calamity. So, what should he do? His thoughts were scattered.

Salah decided at first to knock on the door and wait, or rather, sneak a peek inside the house. If he noticed that she was the one heading to open the door, he would run away and disappear somewhere. It was past midnight, but a light emanated from one of the lower windows. He summoned all of his strength and knocked gently. His nerves were at their highest level of tension. His heartbeat was racing. He saw that a woman was heading to open the door. Was it his mother? Should he flee and hide somewhere? But bewilderment paralyzed his ability to think and move. She opened the door and asked, “Who are you?” He replied, “I am your son.” She was stunned. “My son from where?” “Your son Salah,” he said. She stared at him, and it seemed that she was unable to speak or even think. After a while, she turned around and left him standing there. She left the door open and entered her sleeping children’s rooms, shouting, “Wake up! Someone says he is your brother!” Salah took a few steps inside the house.

They gathered around him. He had difficulty recognizing them. When he was abducted, they were just little children, and now they were young men, some of them with beards and mustaches. They, in turn, stared at this stranger, thin as a thread, pale, and sad. In a split second, the eldest threw himself on him, cheering and yelling, “This is my brother Salah! This is my brother Salah!” The brothers were hugging each other. The mother yelled, “I know my son’s body. He has a mole on his left shoulder.” She removed his shirt, saw the mole, and then collapsed in tears.

Salah told me that afterward, he could no longer understand what was happening around him, and everyone became engaged in heartfelt collective weeping.

When the Berlin Wall Fell…

I was born in a village on the outskirts of Casablanca, where I first attended school. My memories still hold onto aspects of the farmers’ lives, especially their folk songs. Their sincere and unpretentious singing expressed a plethora of emotions, including nostalgia, pain, love – life with all its harshness and mystery. My father was a farmer, but after his death, when I was a little child, we moved to the city, where I became involved in political work at an early age. The leftist revolution of the 1970s swept up my generation and left many victims in its wake. The “Years of Lead,” as they were called in Morocco, saw tens of thousands of people imprisoned, exiled, or killed during popular uprisings. I spent a short period in prison, but my experience pales in comparison to those who were sentenced to death or life imprisonment, or who were forced into exile.

This painful period ended, but its scars continue to linger in the individual and collective memory. When the Berlin Wall fell, the Moroccan government declared that it wanted to turn a new page and achieve historical reconciliation. It acknowledged the violations of human rights committed in the past and sought to compensate the victims and offer apologies. It also sought to reconcile with women by passing laws that would protect their rights, and to recognize the Amazigh language and culture and provide ways to promote and integrate them into the media and public life.

When the Berlin Wall collapsed, I–like many others–felt a sense of disappointment and despair. The dreams of revolution, which had opened our eyes, had evaporated. All our ideas and expectations were scattered. In these circumstances, I decided to return to the classroom. After completing a law degree, I enrolled in a journalism institute in Rabat. That’s how I entered journalism from the field of politics. In early 1993, during my time as a journalism student, the National Conference on Media and Communication was held. The state wanted to use this conference to emphasize its commitment to accepting democratic reforms within certain limits. The debate was attended by the Minister of the Interior and Media, who had great power and influence in the government. Ironically, the ministry combines two sets of government functions that should be kept completely separate. The discussion was also attended by leaders and representatives from opposition parties, and by editors of party-affiliated newspapers. Dozens of journalists and civic activists also attended, although their presence was not given equal weight to that of the government and opposition representatives.

At the opening of the conference, the Minister of the Interior and Media read a royal message calling for “developing the national media and making it keep pace with the political changes.” The message also emphasized that since the end of the Cold War and the ideological conflict between East and West, communication had become increasingly important for the aspirations of the world’s peoples for freedom, security, and peace. The message stressed that the conference was held “under favorable conditions for our democratic process, characterized by dialogue, exchange of ideas, and service of the public good, at a time when the rule of law is strengthened, and the reputation and position of Morocco are enhanced on the world stage.”

After the reading of the royal message, the opposition leaders attending as journalists strongly appealed for separating responsibility for the media from the interior ministry in order to ensure the independence of media institutions and provide legal and institutional conditions that would enable journalists to perform their duties in an atmosphere of freedom and security, and away from all forms of state pressure and control. They emphasized that all of this would help develop democratic life.

However, politicians spoke without giving journalists the floor. This indicated that the event, at its core, was political and had political implications. Nonetheless, this negative aspect could be overlooked when we think about the recommendations that resulted from the debate, which can be viewed as a political vision with professional content on how to reform the media. Overall, the event served as a milestone in the process of reconciliation between the government and the opposition.

It is natural for a country aspiring to democratic transformation to be dominated by political concerns, which was noticeable during the “debate.” Therefore, the central focus of its recommendations was political, or had political dimensions that were not hidden, such as talking about freedom and lifting the government’s and its agencies’ control over public media. Secondarily, the recommendations addressed the need to consider the country’s political and cultural diversity, and the importance of supporting regional media and those that speak the Amazigh language. The recommendations did not include a comprehensive discussion of media diversity as a concept.

In Morocco, the media is part of politics, as is the case in all North African and Middle Eastern countries. I transitioned to journalism from politics, carrying my dreams and idealistic values. Politicians draw the lines of liberation and control, while journalists execute them. It took me some time to discover this bitter truth. After graduating and becoming involved in professional practice, I had to learn how to utilize every single opportunity to help me escape from the domination of politics and its agendas. I found refuge in memories, in the forgotten, marginalized, and excluded. I published my first book, which was called “The Farthest Left in Morocco – A Noble Struggle Against the Impossible.” Then, years later, I created my radio program, called: “Zaman Al-Haky” (The Storytelling Era).

Morocco: A Country of Diversity

Throughout its history, Morocco has been a diverse country. It is a geographical crossroads, where Africa meets Europe. While sitting in a café in Tangier, you can easily see with the naked eye the Spanish town of Tarifa across the water. The Mediterranean Sea has had a profound cultural impact on the country. This is the land of Tamazgha, which extends eastwards to the Egyptian borders, and southwards to the coastal countries, and even includes the Canary Islands. This is Morocco, a mix of Arab, Amazigh, Islamic, Hebrew, Andalusian, African and Mediterranean identities.

When France occupied Morocco in the early twentieth century, they wanted to ignite conflict between these different elements, especially through what was called “the Amazigh policy”. However, the opposite happened, as a national movement was formed from the entire society with their different ideologies and backgrounds, and the desire for unity in confronting the colonizers prevailed. It was emphasized that Morocco has one identity based on its Arabic and Islamic foundations, which led to the erasure of all manifestations of diversity.

But after the declaration of independence in 1956, and the birth of the modern state, this unifying approach, which reduced the national identity to its Arab and Islamic aspects, became a constraint on the development of a more openly diverse society. The oppressed and marginalized groups began to express themselves, albeit tentatively, through limited media outlets. There was a dominant radical left at universities and in youth circles, a cultural movement that sought to restore popular culture, and the formation of the first Amazigh associations and the first nucleus of the women’s movement. This cultural and political process continued from the early 1970s until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and was accompanied by widespread repression.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the state made limited amendments to family law and committed to teaching Amazigh in primary schools and broadcasting television news in the Amazigh language. These were modest steps. The state’s main concern was to position itself in a post-Cold War world and promote slogans about democracy and human rights. The authorities attempted to settle serious violations of human rights in order to encourage opposition groups, particularly the Socialists, to participate in the government. The Amazigh and women’s issues, although they began to gain media attention, seemed secondary compared to the direct political issues. However, overall, spaces of freedom began expanding, and public debates started to touch on the prohibited and forbidden, especially when the second channel 2M and independent newspapers began to emerge.

By the end of the 1990s, these massive transformations led to the ascendence of the socialist leader Abderrahmane Youssoufi, whose aim was to achieve a democratic transition. Then a royal speech fully recognized the Amazigh as a national language and culture. A new family code was then issued, leading to the formation of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission, which was responsible for investigating serious human rights violations. Hearings for the victims of these violations were held and were broadcast live on radio and television channels.

In this atmosphere, I joined the national radio and experienced all this political and media transformation, with all its noise and contradictions. I was part of the trend that sought to expand the spaces of freedom and establish professional practices that respected the intelligence of the news audience and represented a break from the old sterile, empty, and opportunistic official discourse. However, it was not always easy.

Even with the departure of Abderrahmane Youssoufi, whicho was considered a failure in the attempt at a democratic transition, the dynamics of political and media openness continued, whether through independent journalism or public media, albeit to a lesser extent. Media attention was particularly focused on the issue of serious human rights violations. Within this dynamic, the audiovisual sector was liberalized, allowing private individuals to establish radio channels, and new channels were added to public media, most notably the Amazigh channel.

Meeting with Milica

One evening, I received a call from a friend who suggested that I meet with a British citizen who was visiting Morocco. That’s how I met Milica, and from there began my journey with the Media Diversity Institute. Over the years, I worked alongside the Institute, which was to me like a great school from which I learned a lot and gained lots of experience. MDI has left a remarkable mark on the Moroccan media landscape through its training courses, which were provided to hundreds of young journalists, and through various other activities and events it organised and hosted. The Institute was able to bring a part of the Anglo-Saxon media culture, especially as it relates to media diversity, to Morocco.

I remember when Milica, along with the king’s advisor and the minister of communication, inaugurated an international conference organised by MDI in Rabat to mark the launch of their activities. Dozens of media experts and journalists from Morocco, Europe, and the Arab world were there. Years later, I sadly recall the evening when a young journalist called me and told me that a headline on the front page of a newspaper read: “Organisation Advocating for LGBTQ+ Rights is About to Form a Partnership with National Radio.” I rushed out and bought the newspaper. The article was clear in its condemnation of the partnership that MDI and the radio were preparing to sign.

When we investigated, we found that the minister of communication—the same person who attended MDI’s opening event–was behind the article, as well as subsequent articles. The minister was a member of the Islamist party that rode the wave of the Arab Spring to reach the government. About a year before assuming his powerful position, he participated in a study trip to London organised by the MDI itself for the benefit of directors of the most important Moroccan media outlets. The delegation visited the BBC, Channel Four, and The Guardian, and attended meetings with British journalists whose focus was on media diversity.

When I met the minister weeks later, I said to him, “You know the Media Diversity Institute well.” In an attempt to evade the topic, he replied, “The partnerships are up to the minister, not the radio director!”

Women and Women

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the tumultuous 1990s in Morocco, the central elite was preoccupied politically, which is understandable in a country striving for a complete democratic transition. This was reflected in the media landscape, where politicians – mostly men – dominated radio and television broadcasts, and their activities and statements dominated the front pages of newspapers. Since then, increasing recognition of societal diversity has been closely connected with the development of progress toward democracy, as demonstrated by the women’s and Amazigh movements. We can say that the recognition of the Amazigh language and culture as an official language alongside Arabic in 2001, and its inclusion in the 2011 constitution, represented a qualitative leap in the development of Moroccan society—a leap that was gradually echoed in media coverage, albeit not to the desired level. The same applies to the issue of women, as after the modest amendments to the Family Law in 1993, the bolder amendments of 2004 followed. Then the 2011 constitution acknowledged in its nineteenth chapter the equality between men and women, the pursuit of parity, and the need to combat all forms of discrimination. However, the presence of women, especially in political talk shows discussing political issues, remains very limited.

I hugged Kenifra and cried together

Mountains and nation sing forever

For dwarves to delve

The city of Khenifra is located in the midst of the Atlas Mountains, which are crossed by the Oum Er-Rbia River. Most of the population in the area are Amazigh speakers. Here are the Zayanes tribes that bravely resisted French colonization, but they did not benefit from the blessings of independence.

In the early 1970s, when a wing of the radical leftist opposition decided to launch an armed revolution, they chose the Middle Atlas Mountains as their base. When the leader of the revolution, Mahmoud, and his comrades were besieged inside one of the houses, they refused to surrender. They fought until their ammunition ran out and chose to die standing.

I pulled over the car on the road from Rabat to Marrakech. I turned on the radio and the voice of Al-Hassania came out. Whenever I listen to her songs, I am reminded of the Middle Atlas Mountains, Khenifra, Imilchil, and of all the forgotten and marginalized mountainous regions of Morocco. Even though I speak Arabic and don’t understand Amazigh, I can perceive from the voice of Al-Hassania the expression of pain and longing, and I can discern a collective lamentation from the screech of the violin.

I assume that Al-Hassania was born in the early 1970s, and she surely hasn’t experienced those painful events that befell the Middle Atlas Mountains after the failure of the revolution and the subsequent comprehensive repression. Thousands of members of the tribes in the area were arrested and abducted, even though most of them did not participate in the movement, which was crushed in its infancy. Many died under torture in secret detention centers. After three decades, the Equity and Reconciliation Commission recognized the state’s responsibility for gross human rights violations. But certainly, even though Al-Hassania didn’t experience the ordeal, she should have heard a lot about it. I imagine some of the collective memory wounds of the Middle Atlas Mountains find a place in the voice of Al-Hassania and in her melodies.

I continue to drive on the highway, and my memory continues its journey. I cherish the shadow of a woman I once loved, and I recall the touch of her fingers. Al-Hassania’s voice blends with the sorrowful features of that woman’s face. Then, Salah’s face comes to my mind as he stands frozen at the door of his house in that dark night. His mother asks, “Who are you?” – “I am your son.” – “Which son?” – “Salah!” Then, she shouts at her sleeping children, “Wake up, there is someone at the door who says he is your brother.” Why do all these images flood my memory now? And what does it mean to escape to the past?

I presented the program “Zaman Al-Haky” (The Storytelling Era) on Moroccan radio for nearly nine years. I hosted those who took up arms against the colonizers. I hosted “Brika,” an elderly woman who, along with her husband, sheltered the resisters in her house. She still remembered the arrests and those who died under torture. I hosted men and women who tasted the agony of years of gunfire, politicians, intellectuals, and artists from all walks and directions.

This is the rich and wounded memory.

A Conversation with Reem

In contrast to my nostalgia for the past and its wounds, I find my daughter, Reem, singing about what’s happening in the world today. Her fluency in English helps her in that regard. The world is a small village to her. We discuss the recent statements made by the Tunisian President, Qais Saied, about a conspiracy theory that a certain group is planning to change the demographic composition of the country by encouraging immigrants from the South Sahara to come to Tunisia. I am surprised when I watch a conversation on France 24 in which a university professor dares to defend the foolishness and delusions of the Tunisian president.

A social media campaign with the slogan “No to the Africanization of Morocco” has emerged. This campaign has led to clashes in Casablanca with immigrants from the South Sahara. Concerning issues related to personal freedom, such as eating during Ramadan, consensual sexual relationships outside of marriage, homosexuality, or single motherhood, Moroccan media tends to promote stereotypes and preconceived judgments. This issue has been exacerbated by the growing influence of social media.

As I speak to Reem, my opera singer daughter, about diversity and the media, I hear the mournful voice of Al-Hassania emanating from the radio.

*Safi Naciri is a journalism professor at University Hassan 2 and at ISIC, Higher Institute of Information and Communication in Morocco. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Tangier, with research on media and democracy. Naciri is a former Editor-in-Chief at SNRT, Moroccan national radio, where he presented several radio shows. He is a regular contributor to public debates and discussions and has published several publications including The History of far left in Morocco (2004). Naciri is a member of the Arabic Network for the Study of Democracy (ANSD) in Beirut.