By Rini Elizabeth Mukkath, freelance journalist

India, touted as the world’s most populous democracy, has commenced its marathon parliamentary election process which will last almost two and a half months to determine the future governance and leadership of this important South Asian nation. 969 million people, more than 10% of the world population are eligible to vote in the elections. Polling will be held in seven phases, it started on April 19 and will continue to June 1, and the final votes will be counted on June 4.

In a country as diverse as India, with its many cultures, languages, and traditions, the media is critical in disseminating information and promoting inclusivity and understanding among its citizens. However, the current media landscape in India is marred by polarisation and weakened journalistic integrity, presenting profound implications for diversity, inclusion, and ultimately, democracy.

The polarisation of media narratives aggravates existing social divides, hindering any efforts towards inclusivity. When media outlets align themselves with political ideologies or interest groups, they risk amplifying biased perspectives while suppressing marginalising voices from the mainstream narrative. Addressing these challenges necessitates a collective effort to safeguard press freedom, promote ethical journalism, and create a media landscape reflective of a pluralistic society like India.

Journalists covering the 2024 election face numerous obstacles that hinder their capacity to fulfill their vital role in safeguarding democratic values. In an interview to MDI, Dr. R.K. Radhakrishnan, Senior Associate Editor, Frontline Magazine, says: “Every democratic institution has been ransacked. Unless you are on one side, you cannot have a job in the media. Politicians have always picked which media they speak to, but the standards around those choices are frightening and shocking”.

Violence towards journalists and press freedom

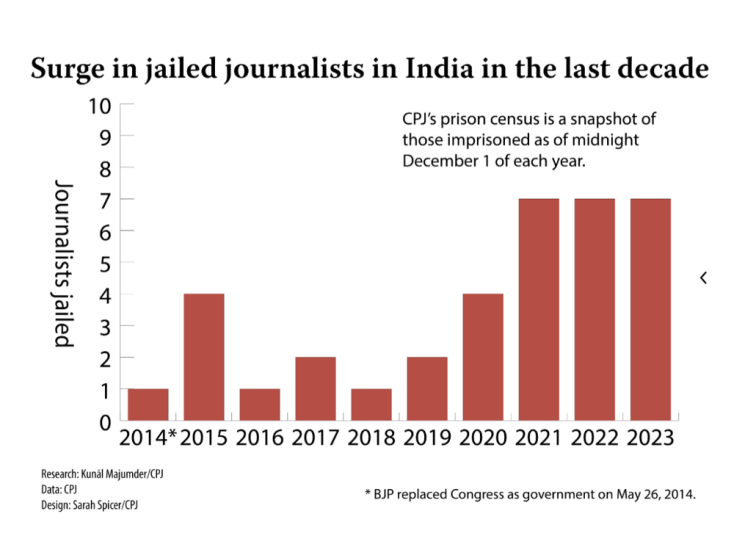

Covering elections in a heavily polarised country is understandably difficult, but a notable challenge has been the criminalisation of journalism, wherein legislation designed for national security is exploited to curtail press freedom. This pattern has intensified in recent years, with a concerning rise in the number of journalists being subjected to legal proceedings and incarceration on charges of terrorism, undermining their capacity to report truthfully and autonomously. According to research by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), “since 2014 a minimum of 15 journalists in India have faced charges under the country’s anti-terror legislation, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. This law permits detention without trial or charge for a duration of up to 180 days”. Speaking to MDI, Kunal Majumder, CPJ India Representative says, “Media is no more the sacred space where there was a certain respect for the messenger. That respect is now going away.”

Media Ownership and Political Influence

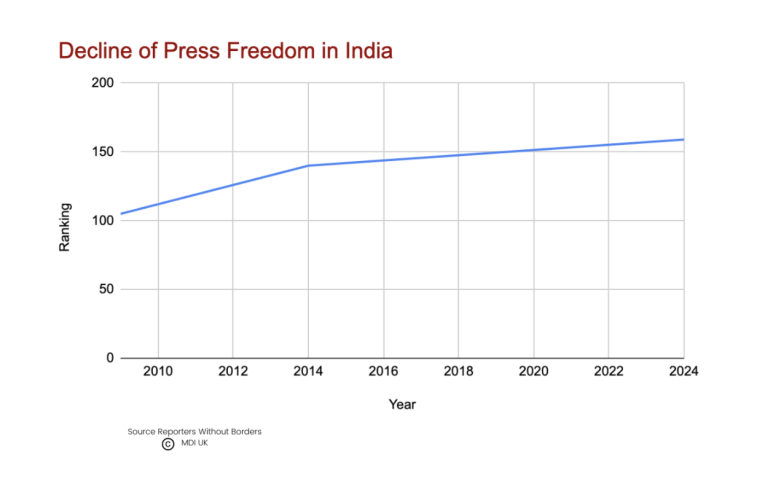

In another troubling trend highlighted by Reporters without Borders (RSF), the acquisition of media outlets by oligarchs with political connections has become increasingly prevalent. According to RSF, “India’s media has fallen into an “unofficial state of emergency” since Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 and engineered a spectacular rapprochement between his party, the BJP, and the big families dominating the media. Reliance Industries group’s magnate Mukesh Ambani, a personal friend of the prime minister, owns more than 70 media outlets that are followed by at least 800 million Indians. The NDTV channel’s acquisition at the end of 2022 by Gautam Adani, a tycoon who is also close to Modi, signalled the end of pluralism in the mainstream media. Recent years have also seen the rise of “Godi media” (a play on Modi’s name and the word for “lapdogs”) – media outlets that mix populism and pro-BJP propaganda. Through pressure and influence, the old Indian model of a pluralist press is being called into question.”

According to Reporters Without Borders, “The other phenomenon that dangerously restricts the free flow of information is the acquisition of media outlets by oligarchs who maintain close ties with political leaders. This is particularly the case in “hybrid” regimes such as India (161st), where all the mainstream media are now owned by wealthy businessmen close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. At the same time, Modi has an army of supporters who track down all online reporting regarded as critical of the government and wage horrific harassment campaigns against the sources. Caught between these two forms of extreme pressure, many journalists are, in practice, forced to censor themselves.”

Erosion of trust

The lack of trust between Government and media has become more evident in recent years making it further difficult for journalists to gather information to educate voters on the major issues plaguing the country, but this was not always the case. “For decades, not a single journalist was imprisoned—a testament to our tradition of press freedom. We have upheld a rich journalistic heritage, with families engrossed in multiple newspapers daily. Our freedom movement saw leaders emerge from editorials, embedding a culture of inquiry and accountability.

Yet, recent years have witnessed a distressing erosion of trust, fuelled partly by genuine grievances and partly by political manipulation via social media. The current Prime Minister’s avoidance of press conferences underscores this shift, while online challenges further complicate the landscape. The need for a vigilant press has never been greater, amidst these turbulent times,” says Majumder.

The apparent break in open communication between the media and the Government has led to increased distrust and fear. “There used to be a time when journalists and politicians could disagree, but people knew it was a journalist’s job to ask the tough questions but now everything comes with a consequence, so journalists have to be careful and there is self-censorship,” adds Radhakrishnan.

Women in Journalism

The rise of women’s participation in news media is commendable, yet it’s overshadowed by an alarming increase in threats they face. “Rape threats, death threats, and constant harassment plague female journalists. Recent incidents, such as the Bulli Bai campaign targeting Muslim women journalists, highlight the urgent need to address toxic online behaviour and protect the safety of all journalists,” says Majumder.

In 2022, Ismat Ara was one of 20 Muslim women journalists whose photos and personal details were posted on an online app called Bulli Bai, which targeted Muslim women. Ara reported it to the police, resulting in the arrest of the app’s makers.

Online toxicity and censorship

The online toxicity not only undermines the integrity of journalism but also poses tangible threats to the physical safety of journalists, as online threats can escalate into real-world violence. “The media landscape in India is polarised, with journalists labelled as “anti-national” and facing arrests or harassment for their reporting,” adds Majumder.

India has also faced increasing criticism for its internet shutdowns and censorship practices, with government pressure leading to the removal of millions of videos on platforms like YouTube. A recent report by Access Now and Global Witness called “Votes will not be counted: Indian election disinformation ads and YouTube,” found that YouTube is approving ads purporting baseless allegations of electoral fraud, lies about voting procedures, and attacks on the integrity of the electoral process. The ads submitted as part of the investigation were withdrawn before publication to ensure they did not run on YouTube.

With India having the highest YouTube user base globally, this failure raises serious concerns about electoral integrity. The investigation urges YouTube to take immediate corrective actions, including thorough evaluations of ad approval processes and increased moderation of election-related content, to prevent further dissemination of misinformation during this crucial period.

Despite these challenges, the role of the media in the democratic process, particularly during elections, remains paramount. Journalists serve as the watchdogs of society, tasked with scrutinising politicians and ensuring transparency in governance. However, the increasing polarisation of politics in India poses a significant threat to media integrity and journalist safety. Without a free and independent media in India, the democratic process is at risk of manipulation and abuse.

Towards a resounding victory for Modi

The legislative body of India, also known as the Lok Sabha (Lower House), is made up of 543 seats, and its members serve a term of five years. To establish governance, a party or coalition must attain a simple majority of 272 seats. In the last elections of 2014, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, secured 303 seats, while the principal opposition party, the Indian National Congress, won 52 seats.

Modi is now in pursuit of a historic third consecutive term and is hoping for a resounding victory for the National Democratic Alliance, spearheaded by the BJP. Modi underscores the significance of a victory saying it is necessary to propel India from its current middle-income status to a developed economy by 2047.

The BJP garners its primary support from the Hindu community, constituting 80% of the nation’s 1.42 billion population. Earlier this year, Modi fulfilled a significant party pledge by overseeing the construction of a grand Hindu temple on a contested site, further solidifying his support base. The BJP relies on the charisma of its political leader Modi whose powerful oration invokes sentiments of nationhood and a Hindu-state. “The BJP has been talking about development by 2047. It is working on the Modi magic, kind of telling the people to have faith in Modi who can solve all their problems.” says Radhakrishnan.

Pictures from shutterstock.com

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Media Diversity Institute. Any question or comment should be addressed to [email protected]