By: Aina Khan

Since I was a girl, Ramadan has been a spiritual retreat from the chaos of daily life.

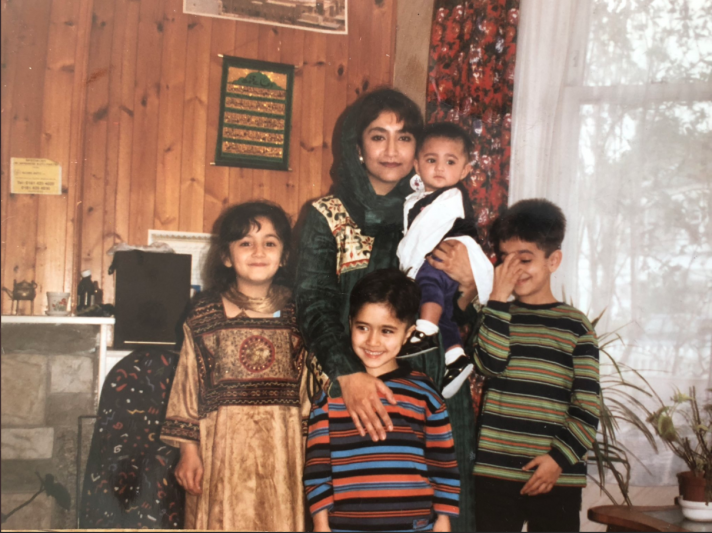

Every morning, I used to shuffle downstairs to the kitchen, puffy-eyed and half-asleep. Like my grandmother before her, my mother would turn on Sunrise Radio, the official aural accompaniment for those excruciatingly early Ramadan breakfasts. Launched in 1984, the Urdu-language radio station was a comforting reminder of home for my grandmother’s generation who migrated from Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, and found themselves thrust into the unfamiliar industrial towns and cities across the country. Now, their grandchildren call those strange British towns home, but we still listen to the Sunrise Radio jingle that proclaims itself to be “the greatest Asian radio station in the world!” as we gather to celebrate Ramadan three generations later.

If it wasn’t the legendary Indian singer Muhammad Rafi’s voice welcoming the month of forgiveness and mercy, the soothing cadence of radio presenter Maher Khan’s voice would beguile her listeners with incandescent prayers—even if, like me, they didn’t understand Urdu. For my family, the day could not begin until she had anointed the fast.

As iftar approached, the dining room would become a flurry of activity as my siblings and I raced to set the table with ruby coloured pomegranate, slices of honey-dew melon, mangoes (Pakistani of course), roast chicken, rice and chickpeas, and a mandatory triple chocolate layer trifle.

We’d flutter to the dining table like moths to the flame, heads bowed, hands raised, as Maher Khan once again guided us hunger-stricken wayfarers, through our prayers. First, we thanked God for the mountains of food spread tantalisingly before of us, before joining her to ask for forgiveness. Finally, the call the prayer, the azaan, sounded, and we could break our fast.

There is a rootedness that comes from eating with family, a connectivity that I felt praying with strangers every evening at the mosque. I felt a renewed intimacy from speaking to God directly, whether it was about fulfilling sophomoric requests for Aragorn from the Lord of the Rings trilogy to become my future husband, or protection for my family and friends from the sorrows of the world. Later, as my journalistic aspirations developed, my prayers became more ambitious, asking that my writing could become a Weapon of Mass instruction in a post 9/11 world where expressing our religion felt fraught with suspicion and dehumanization. It was these moments that were the beating heart of Ramadan.

This year, for the first time in twenty-eight years, I will be spending Ramadan completely alone, in the midst of a global pandemic.

Unlike the hysterical claims of the far-right from India to the UK, shrieking about Muslims embarking on a #CovidJihad to purposely defy social distancing rules and consequently spread the deadly Coronavirus, mosque halls across Britain will be empty this year. There will be no communal iftars where we break our fasts together, or taraweh prayers to look forward to in the evenings. Regulars at the mosque, like the old men with their violently orange henna-dyed beards who praise God as they slide each bead of their tasbir will have to worship from the safety of their homes. As she too self-isolates, Maher Khan will not be guiding listeners through their prayers with her luminous voice this year.

But even if the Coronavirus has materialised the apocalyptic stuff of nightmares, all is not lost. For many like me spending it alone, this year Ramadan will be a digital—and perhaps equally revelatory–experience.

For one, Zoom and FaceTime have become a vital lifeline for religious communities. Bar Mitzvahs, Vaisakhi and Easter celebrations have gone online. The Jewish community celebrated Passover with virtual “Zeders” this year and members of the Christian community marked Easter with loved ones over FaceTime. And now it will connect families and friends for iftars and taraweh prayers. From New Haven to Bradford, religious leaders around the world are using innovative forms of technology and social media to deliver uplifting sabbath speeches on Jumah, and hold weekly zhikr sessions. In the run up to Ramadan, my friends have even roped me into taking part in Islamic history pop quizzes over Zoom–the love for ‘pub quizzes’ is inscribed in our British DNA.

Sure enough, digital connection is only a smartphone supplement for tangible human touch and the warmth of another’s physical presence. I haven’t had a face-to-face conversation in nearly five weeks. But as much as Ramadan is about appreciating the luxuries in our daily lives, the connectivity with community and family, it’s also a religiously sanctioned month of self-care.

This is not the Instagram fetishization of ‘self-care,’ a few drops of positive quotes in cursive fonts as a panacea against a suicidal work culture that demands productivity at the cost of everything else. It is a chance for Muslims to retreat inwards and consider our place in the world. It is enthused with a spirit of activism and gentle reckoning that compels us not to lobotomise our brains with Netflix (although God knows a dose is needed every now and again), but to embrace our role as agents of change. Now, more than ever, it has become clear that even the smallest act of kindness towards others–and towards ourselves–can make all the difference. Across the country, from the first frontline doctors to die of corona virus, to a young Muslim couple in Glasgow who have been giving out facemasks for free, British Muslims are rallying to fight a pandemic which has disproportionately impacted minority communities in the UK.

When the first words of the Quran were revealed by the angel Gabriel during the very first Ramadan in the seventh century, the prophet Muhammad was ironically also in self-imposed isolation—though his was in a cave atop a mountain in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, rather than a six floor walk-up in Croydon.

I haven’t received any divine revelation of my own, but this enforced stillness has made me realise what I’ve known for a while: somewhere between pursuing a part-time master’s degree, and full time work out of a misguided sense of proving my self-worth, I’ve lost myself in the rat race. As the sound of ambulance sirens shriek past my window every thirty minutes, reminding me of the pandemic that has crept into my city, I reflect on the words of the late American writer, James Baldwin.

“The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all of our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.”

Perhaps this Ramadan will be bitterly isolating, quarantined with a succulent plant and a gangly spider as my only living company. Still, the pandemic is proving to be a powerful reminder of how vital journalism and storytelling can be in a world that is collectively and vicariously grieving not just the loss of loved ones, but the loss of our own selves. As I use the time to look inwards, this Ramadan, unlike any other I’ve experienced before, the real prize I hope, is to find myself again.