By Angelo Boccato

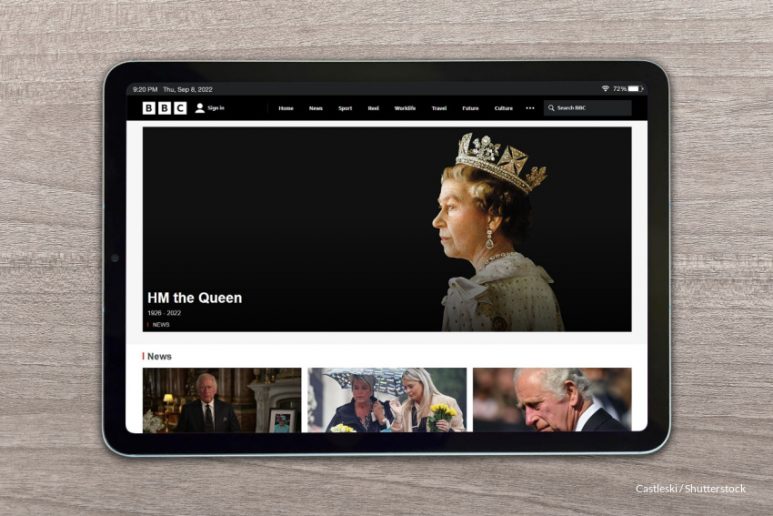

In the days that followed Queen Elizabeth II’s passing on 8 September, some critical reactions started to manifest in the country and abroad. These reactions were strongly connected with the non-stop news coverage of mourners’ queues and royal rituals. The continuous coverage also resulted in media ‘short circuits’, such as the one that involved Sky News and the protest for Chris Kaba on September 10, which was portrayed on the network as a walk of mourning for the Queen and in support for King Charles III.

‘I think it shows very revealingly and clearly how much the media just falls into a sort of establishment pattern; how much the media is not this independent thing that it claims to be in Britain, but it is, sort of, part of the state. Mainstream media is an additional branch of the state and it does state propaganda in a way that it won’t even think about what it is doing,’ Moya Lothian-McLean, contributing editor at Novara Media tells MDI.

The continuous coverage that followed the Queen’s death indicates the British media assumption that this is what the public expected and thus, their coverage was framed accordingly.

‘There’s an unconscious slipping; the Queen died, so they assume this is what the public wants to hear and will feed that instead of interrogating if this is what we should be reporting on 24/7. This is a strange ‘snake eating its tail’ moment, where mainstream media assumes that’s what the public want, so they feed that to the public but that’s not the purpose of the media,’ Lothian-McLean adds.

The media’s lack of critical and independent reporting became obvious with Sky News speculation that the protest about Chris Kaba’s murder was a march in support of the monarchy.

‘[The media] was unaware that a March was even happening for Chris Kaba, so they just assumed that was [about the Queen]. There is no critical thinking, there was the automatic assumption that of course this is what’s going to happen – there’s going to be people turning out for the Queen,’ Lothian Mc-Lean continues.

The way Chris Kaba’s was covered – or more precisely not covered – was very disturbing. Two years after George Floyd’s murder, the murder of a 24 year old Black man by the police alongside the protests that followed has been obscured in the British news cycle the way it did, with few exceptions.

The London-centric coverage of the sovereign’s death by the British media and the lack of coverage of regions such as Northern Ireland, as reported by Rachel Connolly in Novara Media has been rather problematic. In addition, the perspective of Britons of African and Asian ancestry, not to mention the ones from the Caribbean, Africa, and the indigenous peoples from Australia or the First Nation in Canada, finds even less space on British media.

While foreign media outlets looked at the negative aspects of the British monarch, such as Kehinde Andrews’ take on MSNBC, the British media seems to have followed a one sided approach to their coverage.

This different tone in the media’s coverage is also linked to the growing movement for slavery reparations and for removing the British sovereign as the country’s head of state. In November 2021 Barbados transitioned to a republic within the Commonwealth while more and more members of Commonwealth realm seem to be in support of such movements including Jamaica, where Prince William and Princess Kate’s visit in March was met with calls for reparations and protests, as well as in Antigua and Barbuda, and in the Bahamas.

In the UK, several citizens who expressed republican sympathies have been arrested, in a disturbing development, which has led to questioning the attitude of the police, something that Lothian-McLean explained on Al Jazeera Plus.

Police have arrested several people in the UK for protesting King Charles and the monarchy after the death of Queen Elizabeth II.@mlothianmclean explains how the police have been able to crack down on protesters and repress the right to free speech. pic.twitter.com/5iD19rms2u

— AJ+ (@ajplus) September 15, 2022

‘In the last weeks there has been a lot of condemnation of the Queen which connects her with the suppression of the Mau Mau and also atrocities against other peoples, like in Aden. These are real events with a long and lasting imprint. In the case of India, there are the massacres in the 19th century and the so-called Jallianwala Bagh incident, in which British forces, which also included lots of Indian soldiers, fired and killed hundreds of people in an enclosed space in the town of Jalandhar,’ Dr.Subir Sinha, reader in Theory of Politics and Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies tells MDI.

Dr Sinha talks of the trauma that such events have caused to the people who come from Britain’s past colonies.

‘For those of us who come from the ex-colonised world, these are very traumatic events and they have very lasting effects. The Crown could have come in later and apologised, as part of truth and reconciliation, if you like, and that would have been a very good gesture and one that could have separated, more easily, these events from the Crown. It would at least have some semblance that these atrocities were recognised and they were apologised for. I think this would have done perhaps a lot of good in terms of, not so much sanitising colonialism but, acknowledging what actually happened during that time, because it’s the full domination of another society, the full use of the resources, and the populations of those societies for the primary benefit of the colonising power, Britain, and it is to leave a whole range of problems’ Dr Sinha continues.

Britain’s colonial legacy can be seen clearly in former colonies’ law as well as their insitutions. Although the media look at these issues from time to time, an in depth look of Britain’s role is missing.

‘Laws banning homosexuality in parts of Africa during colonial rule, can be traced back to certain colonial laws that have resulted in these kinds of bans. Secondarily, the laws concerning sedition were initially designed to stop the momentum of the anti-colonial movement, but if you look at the situation today, you could have written articles criticising the government in India or you could be a part of a social movement, and, for this, you could be arrested under super sedition laws that were put into place in the British colonial period,’ concludes Sinha.

While the low number of journalists of colour in British newsrooms constitutes a part of the reason why diverse conversations on the Queen, the royal family, race, class, and the Empire can hardly find space in the media discourse, the momentum cannot be stopped.

Academics, journalists, and activists from Britain, and beyond, are calling for a different conversation on history. This conversation should be safe from sanitising popular culture approaches in the style of Downton Abbey or The Crown. Finally, the way education is approached needs to change and the future of the monarchy itself should be examined through a progressive lens both in the UK and abroad.

Photo Credits: Castleski / Shutterstock