By Joy Francis*

This essay is from the upcoming book to mark the Media Diversity Institute’s 25th anniversary. The book consists of essays by academics, journalists, media experts, civil society activists, and policymakers – all those who have supported us in our work towards diversity, inclusion, and fairer representation of marginalised and vulnerable communities in the media. The paper version of the book will be launched at the Anniversary celebration on the 17th of November 2023 in London. Watch this space for the other 24 essays.

When I was introduced to Media Diversity Institute (MDI) founder Milica Pesic in 2000 by Freedom Forum Europe director John Owen, the print and broadcast media were facing growing scrutiny over their lack of commitment to racial diversity.

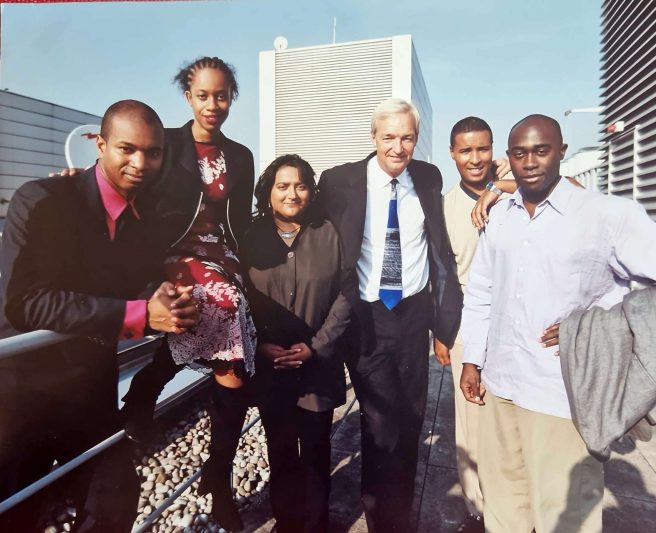

It was also the year when I and four other black and brown journalists – Paul Macey, Veena Josh, Henry Bonsu and David Gyimah, officially launched The Creative Collective, a media and organisational development consultancy for this very reason.

We were galvanised to collaborate by the main finding of The MacPherson Report (1999) into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence on the 22nd April 1993: that the Metropolitan Police was ‘unwittingly’ institutionally racist.

We were also perplexed at the absence of any media censure over its own racial bias, which was painfully evident with the initial gaslighting of Lawrence’s murder. Garnering minimal coverage in the local press, the public was deprived of the chance to emotionally connect with a life cut short through a heinous act. Instead, black people were once again left with the message our lives didn’t matter.

As practising journalists of colour, most of us worked in overwhelmingly white, middle class newsrooms. We wanted to challenge the single [white] narrative and unspoken status quo at the heart of mainstream media reporting. We didn’t want to collude in our misrepresentation. Lawrence could have been my brother or cousin. It hurt and was triggering. Racism was our lived experience. We wanted, and deserved, meaningful change.

Meeting Pesic was a breath of fresh air. We instantly bonded over our respective missions to challenge media outlets (and media literacy) to be more inclusive. Pesic and I were both women, both journalists and both minorities in Britain: Pesic, a Serbian immigrant; me, a London-born citizen of Jamaican parentage.

Both of us had helped create fledgling organisations. MDI was two years old, focused on freedom of expression, reporting diversity in the media, media democratisation and amplifying the voices of civic organisations.

The Creative Collective was months old, yet we were determined to challenge the media’s inability to fairly report the global majority experience. Facilitating third sector organisations to develop their own media platforms and be the lead narrators in their stories was an essential component of that vision. MDI’s focus was international. Ours was UK-wide.

Connecting with Pesic was both timely and apt as that year the Cultural Diversity Network (CDN) launched with 11 broadcast-focused organisations, including Channel 4, to address race, class, disability, religion and belief, gender and ageism inequities.

The CDN Diversity Pledge, supported by 200 production companies, provided a process of accountability where signatories agreed to “take measurable steps to improve diversity”. If an independent production company didn’t sign up to the pledge, broadcasters were given the agency to refuse to commission them.

Meanwhile, tumbleweed rolled uninterrupted down Fleet Street as minimal progress was being made by newspapers to address the lack of diversity in their newsrooms. At the time, data on the number of journalists of colour, the roles they held and where they were geographically based wasn’t being collected or published. Ethnic monitoring and exit interviews, anecdotally, weren’t commonplace, nor was engaging with the growing public debate and dissatisfaction over the lack of media diversity.

A common belief doing the rounds in industry circles was that there weren’t enough talented journalists of colour to be recruited. A view that was reinforced through our interviews with black and brown journalists who had left print journalism for publishing and broadcasting. Conversations that were later mirrored in discussions held with some national newspaper editors.

This unaccountability motivated me and my Creative Collective co-founders to act. After forming an alliance with Freedom Forum Europe and John Owen, I was invited to a week-long field trip to be an ‘Observer’ on Freedom Forum Washington’s Chips Quinn Memorial Fund for Minority Scholars in Journalism. I spoke to and interviewed East Asian, South Asian, African American, Hispanic American and indigenous journalism scholars.

Without exception, each scholar was surprised and excited that I was from England. “I didn’t know there were black people in Britain” was a common refrain. To many, I was from an unheard species called Black British journalist. My heart sank. The CBI, British Council and the British media clearly weren’t doing a great job reflecting the true diversity of Britain.

My presence reinforced the now universal mantra that representation matters, especially as virtually all of the Chips Quinn tutors, many of them Pulitzer Prize winning journalists and editors, were white. A reality that was publicly acknowledged by the organisers and journalists themselves as evidence of the newspaper industry’s legacy of whiteness which the programme was seeking to redress.

At the end of the trip, I was invited to meet the Freedom Forum board. After a lively conversation with Chips Quinn’s founder John C. Quinn, I was unexpectedly offered $10,000 seed funding for The Creative Collective to launch an adapted version of its successful programme, which had already put 500 budding journalists through newspaper internships.

Convinced that British newspapers were a “tough nut to crack” on diversity, and unlikely to fund an internship, the only stipulation was that we secure three newspapers to match fund bursaries for three to six-month internships.

Once back on English soil, we worked to secure support for the programme. Channel 4 News lead anchor Jon Snow, New York Times political correspondent Jonathan P Hicks and Guardian correspondent Gary Younge didn’t take much persuading. The National Union of Journalists and London College of Printing agreed to be partners.

We visited journalism schools around the country and spoke to journalism tutors and students of colour to understand the challenges they faced as once they qualified, many didn’t transition into the print media. The few who did weren’t being retained.

Every single national and regional newspaper in England was invited to be part of The Creative Collective National Print Media Internship scheme. The overwhelming majority ignored us. One national newspaper, that shall remain nameless, returned the full information pack back to us. The initial signs weren’t promising.

Our launch on Monday 15th January 2021 got press traction nationally and regionally, including in The Guardian and Press Gazette. We beat our target of three newspapers by securing The Times, Nottingham Evening Post, Manchester Evening News, Bradford Telegraph and Argus and The Big Issue. It was also timely as the week before, BBC director general Greg Dyke agreed with a BBC Radio Scotland presenter’s description of his corporation as “hideously white”.

Bradford Telegraph & Argus Editor Perry Austin-Clarke signed up because he wanted his newspaper’s staff to be more representative of the local community. “We’re not looking for more journalists from the ethnic minority communities so that they can cover only ethnic minority affairs. It’s long been our policy that all our journalists are here to serve all our readers, whatever their ethnic background.”

The Financial Times, Supply Management and Scunthorpe Telegraph joined in year two. All the newspapers and publications stayed with us, and we secured additional funding through sponsors from the NGO and public sectors. In three years and three rounds, over 22 journalism students were recruited to the programme as some newspapers took on two interns at a time.

After every internship, the majority of the interns were offered full time positions. Those who accepted worked at The Times, The Big Issue, Financial Times, Manchester Evening News and Nottingham Evening Post.

Over 60% of the interns went on to have a career in the media, both here and abroad, from Al Jazeera, The Mirror and Marie Claire South Africa to Community Care magazine and BBC Radio and TV. The scheme was cited as a model of good practice in the Society of Editors Diversity in the Newsroom report (2004).

Goldsmiths, University of London, in partnership with The Financial Times, established a diversity bursary fund for BAME students to enable them to complete their studies. The internship scheme was selected as a top 30 media diversity initiative by the European Commission in 2009, and from 2006-2008 we adapted the model for Transport for London’s press office, which became a rolling programme.

While running the internship programme and fielding positive (and negative) responses from the print media and right-wing opponents, I was still a practising journalist. Within a year of being established, The Creative Collective showed what was possible with a small team, an even smaller budget and a growing ecosystem of collaborators, bolstered by a targeted media and recruitment campaign.

It was ironic that I had to secure American money to run a national print media internship programme for journalists of colour in Britain. It was also telling that our programme targeted journalism students of colour who had already beat the odds to be part of the 1% on newspaper and periodical journalism programmes, only not to transition into a newspaper career, which they paid to study for.

Instead of attracting journalists of colour, large swathes of the print media did very little to become transparent. Many journalism jobs weren’t widely advertised as they are now. Unpaid internships were rife, affordable only to those with money. Professionally, newspapers were viewed as an unattractive and culturally unsafe option for people of colour. Word of mouth about discriminatory experiences in the newsroom was enough to stop students of colour from applying for the sake of their wellbeing.

By 2002, I chose to run The Creative Collective full time. I knew that change wouldn’t happen quickly enough while working inside the industry. The newsroom was a microcosm of wider society, which meant I had to be in the world, with more independence. Part of that pivot was a desire to work directly with the communities under fire, including Muslim communities who were a growing target for inflammatory coverage and Islamophobia in the wake of the 9/11 attacks against the US in 2001.

I kept my hand in the game as a contracted freelance broadcast and print journalist and journalism lecturer. One of the pieces I wrote for The Guardian reflected on the impact of two high profile race discrimination cases brought against the BBC.

One of the complainants, World Service broadcaster Sharan Sadhu, spoke of the “colonial culture” and boys club. Coming a year after Greg Dyke’s “hideously white” admission, it signalled loud and clear that “recruiting ethnic minority staff without attempting to nurture and accommodate racial and cultural differences doesn’t work”.

While researching the piece, a black female journalist who had freelanced for the BBC for more than three years said: “There is this unspoken reality that, although I look different from you, I must act, think and speak the same as you, which is then promoted as diversity.”

An Asian female BBC producer I spoke to said that her role changed, without consultation, to an “ethnic brief”, which wasn’t in her job description. She was expected to bring in black and ethnic minority stories and was criticised for not doing enough.

The Journalists at Work Survey 2002 by the Journalism Training Forum, and a follow up report in 2012, commissioned by the National Council for the Training of Journalists cut through the lack of transparency for the first time.

They found that the levels of ethnic diversity remained ‘troublingly low’, in an industry where over half of those employed worked in London and the South East – the most ethnically and culturally diverse regions in the country.

Unsurprisingly, the surveys also revealed how unpaid internships were commonplace, making the profession an occupation where social class impacted on the likelihood of entering the industry.

During this time, I was delivering media training and consultancy through The Creative Collective for third sector organisations and NGOs, including the Refugee Council, MDI and Article 19. Working with journalists and editors in former communist countries in the Balkans on understanding intersectionality, the impact of hate speech, the exclusion of Roma people and recruiting women journalists was an eye-opener.

I was unfailingly the only black person in the room. Any fear of having to confront unwelcomed or inappropriate racial tropes was quickly dashed. Unlike my experience in Britain, being black was viewed as an asset. My Black British journalist credentials and navigation of racism and discrimination carried weight. My lived experience was of genuine interest, and I didn’t have to ‘justify’ my presence or thought leadership. What I did have to face was nuanced sexism.

Looking like I was in my mid-20s when I was in my late-30s, there was a tendency to show more deference to the older white male media trainers. When the relevant participants were challenged on this point over social drinks at the end of the programme, lively and honest debates ensued about gender politics in their respective countries.

The experience of working in countries where I didn’t see any people of colour, apart from the occasional billboard featuring supermodel Naomi Campbell, allowed me to experience my blackness and woman-ness through a different lens, which was liberating.

Of course, I was operating in a privileged space with highly educated journalists and activists who prided themselves on their intellectual and philosophical acumen. I couldn’t say the same while in equivalent spaces in Britain. I remember walking through various overwhelmingly white newsrooms in Fleet Street while doing a recce for our internship programme. Not only did I feel like an outsider, I felt my blackness being assessed through a colonially-imprinted lens. I had to ground myself in my value, buoyed by my knowledge, cultural self confidence and activist spirit.

My understanding of why reporting diversity is vital was expanded through my work with MDI. I was exposed to other cultures in their country of origin, often at risk of government oppression. Creating workshops and facilitating civic leaders, human rights organisations, NGOs, doctors and academics in countries like Morocco, Albania, Hungary and Algeria to be media confident was humbling, exciting and life-changing.

Whether it was providing tailored consultancy to a civic organisation’s staff and volunteers over three consecutive days, facilitating a five day programme on how to run a media campaign, developing digital communications strategies on destigmatising HIV or challenging misreporting while being interviewed on live TV, the participants were fully engaged.

They brought their real-life experiences, passions and traumas to the table. They relished the role play and the opportunity to meet and interview real journalists while having the media demystified. They trusted me with their stories, worldviews, and points of difference, all within a structured and compassionate space. At the end, they left with an action plan and a personalised roadmap for change.

Little did I know that my collaborative relationship with MDI would hit another level of impact. In 2011 I was invited to create a Reporting Migration, Race and Ethnicity Module for MDI’s new Diversity and the Media MA, the first of its kind. Hosted by the University of Westminster, the module provided a critical and practical assessment of journalistic practice and the cultural production and representation of race, ethnicity and migrancy in contemporary media, with a particular focus on print media.

During the months spent drafting the module, the Leveson Inquiry – the largest public inquiry in British history – was gathering evidence on media abuse and phone hacking. By the time the MA was launched in 2012, the inquiry was under fire for not robustly investigating discrimination and racism after campaigning from civic organisations, public figures and journalists of colour.

When the inquiry reported in November 2012, Lord Leveson stated that “when assessed as a whole, the evidence of discriminatory, sensational or unbalanced reporting in relation to ethnic minorities, immigrants and/or asylum seekers, is concerning”.

Leveson added that there were enough examples of “careless or reckless reporting” to conclude that discriminatory, sensational or unbalanced reporting in relation to ethnic minorities, immigrants and/or asylum seekers is a feature of journalistic practice in parts of the press, rather than an aberration.

Dr Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed, in Race and Reform: Islam and Muslims and the British Media, 2012, said: “Research shows that not only do a third of the British population admit to racism but institutional racism is still pervasive in British social institutions from education to the judiciary. Despite regulation, codes of conduct and robust internal procedures, ethnic minorities are still underrepresented in the mainstream media. A picture that has barely improved over 10 years.”

Against this backdrop, the MA was not only timely but ahead of the curve. The curriculum reflected the intersections of gender, disability, faith and racial identity and sexual orientation, and supplied a newsroom, practice-based environment for the status quo and media norms to be challenged.

A key element of the MA, which attracted a diverse range of students (from the UK, Serbia, Egypt, Malaysia, China and Brazil), was to inspire them to transfer the learning to their coverage of ethnic minorities, migration, race and racism in their respective countries. Two of my cohort went on to secure distinctions in their Masters, and 11 years later, the MA is thriving.

My relationship with MDI didn’t end there. I became a MDI trustee in 2016 and have been part of its journey to becoming a significant influence globally, encouraging accurate and nuanced reporting on race, religion, ethnicity, class, age, disability, gender and sexual identity in numerous countries from China to the US.

Since my first interaction with MDI, the language on media diversity has changed, assisted by the proliferation of social media which continues to break stories as an alternative media platform for the global majority.

There is a considered shift away from using the acronym BAME to a multiplicity of hybrid self-definitions, as shown in this piece, including the terms black and minoritised or racialised communities. They all have a place.

Creative Diversity is the new buzz word. Inclusion is uttered as often, if not more, than diversity. The Covid pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of colour, George Floyd’s murder on 25th May 2020 and the BLM global protests inspired many organisations to declare their intention to become anti-racist organisations. The proof, though, is in the pudding.

We are now talking more openly about structural, systemic and interpersonal racism while racial justice and racial healing are part of the under-reported narrative of recovery and reparations as Grenfell and the Windrush Scandal remain unresolved.

Now faced with the fallout of Brexit and the cost of living crisis, we have a government and a national newspaper cluster that are predominantly centre right or right wing in tone. There is a sense that they have bought into Prime Minister David Cameron’s view in 2011 that “state multiculturalism” had failed.

We have a Home Secretary Suella Braverman that sees deporting migrants to Rwanda as her professional dream. News Corp’s chief Rupert Murdoch has been outed for secret phone hacking settlements, including to Prince William in 2020, the very scandal the Leveson Inquiry shed light on back in 2011.

Where light isn’t being systematically shed is on the media’s progress on diversity and inclusion. The Creative Diversity Network and its introduction of Diamond, a single online system used by the BBC, ITV, Channel 4, Paramount, UKTV and Sky to obtain consistent diversity data on programmes they commission, releases its findings annually.

That aside, it feels as if most newspapers and some broadcast outlets are lagging behind. This perception was reinforced in June 2020 when 50 journalists of colour accused UK newsrooms of repeatedly failing to improve diversity in the industry. The Independent columnist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown said that “brilliant” young journalists are being missed because of nepotism, laziness and ignorance from the people “making judgements about who should be there”. They called on the Society of Editors (SoE) to do more.

Unfortunately, a year later, the SoE’s executive director Ian Murray issued an uncleared statement rejecting the Duchess of Sussex’s claim that parts of the media were racist. This led 168 journalists, writers and broadcasters of colour to write an open letter claiming that Murray’s statement proved the SoE was “an institution and an industry in denial”.

The current stalemate at the BBC over its plans to significantly curtail its black radio shows after a sustained campaign in the black press, has raised fears that any diversity gains are being rolled back.

These unsettling developments remind me of a still relevant quote by media and culture academic Dr Anamik Saha from 2017, on the idea of media industry equality being advanced by sector diversity initiatives.

“The inclusion of ethnic minorities within the industry’s dominant whiteness does not necessarily produce a more racially harmonious industrial condition. Black and minority ethnic creatives are often denied autonomy, editorial control, and must exist within an unaltered institutional climate where they remain subjected to various and habitual forms of racism. This suggests that more off-screen diversity does not necessarily produce ‘better representation’ on screen or neatly unsettle industry norms.”

My conclusion is unequivocal. Our work is never done. Thirty years after qualifying as a journalist, and 23 years after meeting MDI’s founder Milica Pesic, I continue to pursue my mission for unheard stories to be told, now as part of Words of Colour, a purpose-driven immersive change agency I co-founded in 2006.

Using the principles of inclusive journalism, storytelling and racial justice, we aim to build sustainable models and ecosystems in different spaces, from universities and theatres to research bodies and publishers, and to develop writers, creatives and entrepreneurs of colour to be change agents.

My MDI journey may have ended in the autumn of 2022, when I stepped down as a trustee to make way for new voices to shape its promising future. But my learning continues.

*Joy Francis is a co-founder and executive director of Words of Colour, co-founder of Digital Women UK and the award-winning Synergi Collaborative Centre. The former print and broadcast journalist is a curator, producer, cultural strategist and longstanding activist for racial equality and cultural inclusion in literature, publishing and the media. She collaborated with the Media Diversity Institute to launch its Diversity and the Media MA at the University of Westminster in 2012. In 2016 she was appointed as the media liaison lead for the Hillsborough Inquests and in 2017 for the Camber Sands Inquests by award-winning civil rights law firm Birnberg Peirce. Joy was elected to the Royal Society of Literature as an Honorary Fellow in 2022.

(Photo credit: Robin Forster)